Well, Well, Well - The New Mormon Apostle Has Defense Industry Connections

The newly promoted British LDS apostle Patrick Kearon has only given three talks during the church’s semiannual General Conference. The most recent two have earned him praise as a uniquely compassionate Mormon leader — he taught that refugees and abuse survivors are worthy of God’s love. His first talk, however, was an unremarkable sermon about strict obedience to the teachings of the Mormon leaders. To illustrate his point, Kearon shared a story about living in Saudi Arabia as a child. His father, Paddy, had warned Patrick to always wear shoes when walking on the dunes. Ignoring his father, young Patrick went exploring wearing flip-flops, and a hiding scorpion stung him through the soft sole. Missing from the talk are any details as to what exactly his family was doing in Saudi Arabia in the 60s and 70s. Turns out, the mission Paddy was part of was a consequential moment in British arms dealing history. Patrick joined Mormonism later in life, and his family never converted, but seeing as the adventure in Saudi Arabia made it into a conference talk, it counts as Mormon history.

Before we set off, a note. If you try to Google Paddy Kearon, you’ll find two other people that share the name. One, Frances Alice “Paddy” Kearon, died the same year as “our” Paddy Kearon. Another Paddy Kearon died in World War II during Operation Source, the attack on the Tirpitz using midget submarines. That’s a fascinating story, but you’ll have to look it up on your own.

*

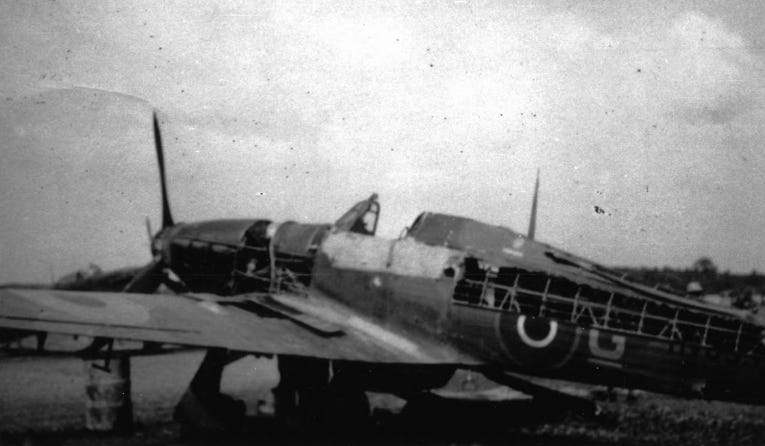

Norman Walter 'Paddy' Kearon’s career with the Royal Air Force (RAF) started in 1939 when he joined as an equipment officer. Details about his wartime service are scarce, but I found a picture of what I presume to be his Hawker Hurricane in a book about RAF fighter pilots in Burma. At some point during the battles in South Asia, Kearon had a close brush with death. While dogfighting with a bomber, Kearon was wounded, and nearly the whole left side of his Hurricane was torn off. The year was 1943.

Kearon next shows up in Germany after the war. RAF officers had commandeered the airfields of the Nationalsozialistisches Fliegerkorps, a gliding club established in 1937 to train young future Luftwaffe pilots in aviation basics. The Fliegerkorps descended from the Deutscher Luftsportverband, a paramilitary organization masquerading as a gliding club. With Germany obligated by the Treaty of Versailles to not build an air force, the Deutscher Luftsportverband allowed Nazi high command to secretly train pilots until the existence of the Luftwaffe was publicly disclosed. After the war the facilities of the Fliegerkorps and Luftsportverband were used by RAF pilots for recreational glider flying.

Why Paddy Kearon ended up in Germany after fighting in Burma is unclear, but given his future significance to British weapons dealing I would assume that he was part of the technical staff to evaluate Luftwaffe weapons, hoping to capitalize on German aerospace technology for a future fight against the Soviets. This theory is backed up by the fact that he did not return from Germany for years. In a history of the Royal Air Force Gliding & Soaring Association, the author notes that in 1951 Kearon, having returned from Germany, became the Senior Equipment Staff Officer for the Association.

The RAFGSA was where Kearon did most of his flying after the war. The organization was a voluntary gliding association, designed to provide RAF pilots and especially ground crew the opportunity to fly recreationally, without all the stuffy structure of a full military aviation force. The first gliders operated by the Association had been captured from Germany after the war.

Composed of old combat veterans and new hands practicing one of the most low-key forms of aviation, the RAFGSA had a decidedly lax atmosphere. Silly (alcohol fueled) times abounded. User “astir 8” on an aviation forum shares the following story of Paddy Kearon:

The story I heard concerned a weekend gathering of GSA members at a certain airfield too many years ago. All were in civvies and happily bunked in together in a vacant airman's dormitory.

On the Saturday night Chinese takeaways and alcoholic beverages had been procured and were happily being consumed, with packaging somewhat scattered around the dormitory when in came God's Annointed, the SWO, who did wax wrathful at the scene and demanded to know who was the senior rank present.

"I suppose that would be me" came an Irish-accented voice [Paddy Kearon] from the back.

"Right, you in my office in five minutes" said the SWO, who departed to prepare a royal b******ing.

"I suppose I'd better put on my uniform then" said the Irish guy.

I understand that the SWO had to significantly change his proposed speech (and possibly his underwear as well) when he found an Air Commodore standing meekly in front of his desk!

In another adventure, Paddy collided midair with fellow glider pilot A.J. Deane-Drummond, a World War II British hero who had escaped Nazi prisoner-of-war camps on three separate occasions. Both men were unharmed, but Paddy had managed to knock 6 feet off one of Deane-Drummond’s wings.

Flying gliders and getting smashed on Guinness was fun, but the RAF was not done with Paddy. Within a decade of returning home from Germany, Paddy was called on for a new mission: saving the British aerospace industry.

The Saudi Arabian Air Defense Scheme

British aerospace found itself in a dire position by the late 50s. Years of economic decline, interservice rivalry, and lack of political willpower left the industry a mere shadow of the massive manufacturing engine that sent fleets of bombers to burn German cities to the ground. This was bad news, for the British desperately needed airplanes to potentially fight the Soviets as well as hold on to their rapidly declining empire.

British air doctrine for nuclear conflict, like many NATO nations in the 50s, relied on high-flying bombers capable of evading Soviet defenses by simply flying above them. However, as the new breed of Soviet interceptors and air defense systems came online, the NATO nations realized that these high-altitude bomber waves would get chewed apart during a conflict. The next generation of nuclear bombers would need to fly low and fast under Soviet radar coverage, evading detection until the last possible moment.

To this end, the British Aircraft Corporation built the TSR-2, a sleek prototype penetration bomber painted in anti-flash white. But the state of the British aviation industry hadn’t improved. Political infighting and slipping performance goals ensured the cancellation of the futuristic bomber. At the same time, the Americans were developing a comparable aircraft, the General Dynamics F-111 Aardvark. Instead of starting work on a new indigenous aircraft, the British decided to buy the F-111. For that, they’d need cash, and the economy was in shambles.

The British administrators of the Middle East were also facing a crisis. After the Suez Crisis, British imperial reach was severely curtailed. Although the empire was handing over its old territory, it still wished to maintain influence over the region, especially its lucrative oil fields. Prime Minister Harold Wilson realized that the British could maintain influence in the Middle East while shoring up their own flagging economy by selling arms, and especially military aircraft, to the regional governments. However, to keep the politics clean, Wilson would pressure corporations to deal with the governments themselves, bypassing the UK Ministry of Defense. To solve the compounding problems at home and abroad, the British needed a Middle Eastern crisis that would pressure a powerful government into buying British airplanes, restoring British power in the region, and raising the cash to buy F-111 Aardvarks to nuke the Soviets.

In 1962, Yemen gave them their opening. A pro-Egyptian faction within the kingdom overthrew the Imam and plunged the country into civil war. Yemeni royalists found sanctuary in Saudi Arabia while Egypt sent thousands of troops to defend the newly minted Yemen Arab Republic. Unfortunately for the Saudis, that meant sending waves of bombers into Saudi territory to hit royalist positions. Traditionally, Saudi Arabia was an ally of the United States, but when President Kennedy recognized the YAR, the princes turned to the UK for military support. Specifically, the Saudis wanted a way to stop those pesky Egyptian pilots from crossing into their airspace.

The British had weapons to sell, and the Saudi princes weren’t really that angry with the US. They were still willing to do business. The US and UK sent diplomatic missions to Saudi Arabia, including Air Commodore Paddy Kearon and his son, future apostle of Jesus Christ: Patrick.

Saudi Arabia was, as another officer told Kearon, the “last frontier” for British weapon dealings. The unified country was only a few decades old and underdeveloped but was sitting on top of massive oil reserves. Money poured into the country after World War II as the various Western powers looked to exploit the kingdom while the Saudi leaders tried to rapidly modernize their nation. With a unitary monarchy the quickest way to the top was bribery and extortion, a game the Americans and British were more than happy to play. Author Andrew Duncan quotes Paddy Kearon himself in the book Money Rush:

It is not a repressive society. All right, there is no parliamentary democracy, but you have something far more effective. Anyone who is patient enough can get to see the head man, and something will be done.

Along with all this came danger. The crown princes were notoriously fickle and the government was violently oppressive. Soviet dealings with Saudi Arabia’s enemies meant the whole region was constantly on the verge of war. Besides these large-scale complications, just existing in the country was a hazard. Saudi Arabia had an atrocious road safety record, tallying 17,000 traffic deaths in one year, twenty-four times the number of deaths in comparable Western countries.

The US, UK, and Saudi Arabia put their heads together and hatched the Saudi Arabia Air Defense scheme. The UK would provide planes for a new air force, the US would provide surface-to-air missile defense systems, and then the UK would use the cash to buy US F-111s. The plan was also called Operation Magic Carpet. The UK decided to send over English Electric Lightning interceptors for the new Royal Saudi Air Force (RSAF) along with Airwork Services, a technical service company. Airwork would train Saudi pilots and service the Lightnings, gradually stepping back to allow the RSAF unfettered control of the planes.

The Lightnings on their own were great, but ended up being one of the weak links in the plan. Born out of nuclear calculus, the airplane came from a requirement for a super-fast interceptor to defend the British home islands. RAF planners expected to rapidly launch waves of interceptors to shoot down incoming Soviet bombers before they could reach the islands — the defense strategy had not changed all that much from the Battle of Britain. English Electric built the Lightning around this mission, wrapping an aerodynamic fuselage around two powerful engines that gave the airplane blistering climb performance at the expense of range. Pilots compared flying it to being strapped to a rocket. Despite being perfect for stopping Egyptian incursions on paper, the Lightning was an intricate airplane, requiring skilled pilots and ground support crew. Training pilots would prove difficult; maintaining these delicate machines in harsh desert conditions, an impossibility.

Still, Kearon and his team pushed on. Defense minister Sultan bin Abdulaziz put Deputy Minister of Defense and Aviation Turki II bin Abdulaziz Al Saud in charge of Operation Magic Carpet and Kearon acted as the liaison between the prince and the UK government.

Operation Magic Carpet went south almost immediately. Airwork had severely overpromised and was struggling to train pilots and maintain the Lightnings, much to Kearon’s chagrin. At times, not a single one of the interceptors was flight-capable or had a Saudi pilot qualified to fly it. Documents from the time show that the British officers spent most of their time trying to get the Saudi crews up to speed while promising the princes that their new air force was just around the corner.

Yet, Egyptian aircraft continued to cross into Saudi airspace. The Saudis needed something to shoot down the Egyptians. To placate Prince Turki, the British hatched a plan. They couldn’t have the Airwork crews fly the planes under orders from the UK government, but if the pilots just so happened to want to fly combat missions themselves, who could stop them? Ex-RAF officer Geoffrey Edwards would act as the go-between, drawing up contracts for the Airwork crew to sign on as mercenary pilots for the Saudis. In practice, the “volunteering” part of the plan was idealistic. Edwards used his powers to all but force pilots to sign the contracts, but many were reticent. Most Airwork crewmen were ex-military — independently fighting for a foreign power could potentially rob them of their pensions and citizenships. And even if Edwards could get the British pilots to fly, maintenance issues grounded most of the Lightning fleet, and you can’t convince spare parts to suddenly appear.

Kearon ran himself ragged, bringing messages to all the different parties, hosting dinners at his home, and trying to placate Prince Turki. Things got more complicated when the Americans showed interest in expanding their role in the deal. Since the British planes weren’t working, Lockheed and Northrop sent notorious arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi to extol the virtues of American aircraft. Khashoggi had a plan to trade oil for airplanes, putting intense pressure on the British to step up their side of the deal. Kearon promised that the Lightnings would work while offering the Saudis even more airplanes: the Anglo-French Jaguar attack jet and Harrier VTOL fighter.

Despite the ongoing problems with Operation Magic Carpet, the Saudis signed one more deal with the British for a new supply of Lightnings and an equivalent number of Strikemaster light attack jets. More airplanes meant the already overworked Airwork crews were stretched even thinner, compounded by the fact that US contractor Raytheon had already snatched up the most capable Saudi support staff. Then, in 1971, the Airwork main office was robbed and in the course of the investigation Saudi police discovered that Airwork crewmen were illicitly selling liquor out of their offices. Up to this point, the British and US delegates had been isolated from the realities of living in a theocracy (they had built little suburban exclaves outside the Saudi cities), but now the full weight of unitary religious law was bearing down on them. To make matters worse, the Lightnings remained in bad shape, and Edwards was still pressuring British pilots to fly the crumbling machines as mercenaries.

The Saudis and the British Ministry of Defense had had enough. They signed a new arms procurement deal in 1973 that excluded Airwork, returning to a more standard government-to-government contract. For their next generation of airplanes, the Royal Saudi Air Force rejected Kearon’s offer of Jaguar attack planes, going with the American F-5 Freedom Fighter instead.

With Operation Magic Carpet winding down, Kearon sent his son and wife back to the UK, staying in Saudi Arabia until 1981 when he was run over by a car and killed. Nineteen year old Patrick dropped out of school and landed a job with a Minister of Parliament. In the 80s, he lived in California with a Mormon family that convinced him to convert. Four decades later and he’s one of the most powerful men in the Mormon leadership echelons.

While still alive, Paddy Kearon gave his assessment of the project, as quoted in Money Rush:

In a perfect world arms-selling would be unethical, but I have no qualms whatsoever about helping to build a defensive force. I would go further, and say that throughout the Middle East we ought to push the sales of arms. It is a highly profitable business, and we must survive economically. If we don’t do it, others will.

In the end, Operation Magic Carpet was a mixed success. The Lightnings never reached their full potential — they weren’t well-suited for the environment anyway. Despite all the effort, the British never got their F-111s. The Aardvark ended up being an expensive boondoggle even for the Americans and the Brits couldn’t get the cash together to buy a fleet. It wasn’t until the 80s that the RAF plugged the strategic gap left by the cancellation of the TRS-2. The airplane they used, the Panavia Tornado, was a collaboration between British, Italian, and German aircraft manufacturers. The Tornado was a sign of things to come; most modern European military aircraft are collaborations between multiple nations. The only export customer for the Tornado was — surprise, surprise — the Saudi Arabians.

That points to the true success of Operation Magic Carpet. While the actual logistics of building the RSAF were messy, the deal provided the nucleus for a new, modern Middle Eastern air force. It also was the start of a lucrative relationship between the US, UK, and Saudi Arabia. The Saudi air force continued to grow, supplied by arms from the various NATO countries, and is now the tenth biggest air force in the world. Despite Paddy Kearon’s insistence that the RSAF was a purely defensive force, it quickly morphed into a cutting-edge strike fleet. Whether it was ever a truly defensive force is, of course, up to debate.

**

We always knew the Mormon church was rich, but until the past decade, the extent of their wealth was never clear. That is until the church began expanding its investment strategy, catching the eye of the SEC. Through filings and lawsuits, the picture is becoming clearer, especially with the release of documents like their form 13-F.

Scrolling through the table, you’ll find that they’ve invested in many different industries. Real estate and tech companies make up a large share of the cash, but there are a lot of defense companies as well. Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin, and L3 Harris all jump out. By my count, the church has hundreds of millions of dollars invested in weapons manufacturing. On top of direct investments, they lease office space to Raytheon and Blue Origin. The latter isn’t a defense contractor yet, but with their New Glenn rocket coming online soon they’ll start picking up Space Force contracts, you can be sure of that. And now Patrick Kearon is one of the top 15 in charge of the whole operation. He’s taken a more circuitous route than his dad but ended up in arms dealing nonetheless.