4 Mormon Connections to the Challenger Disaster

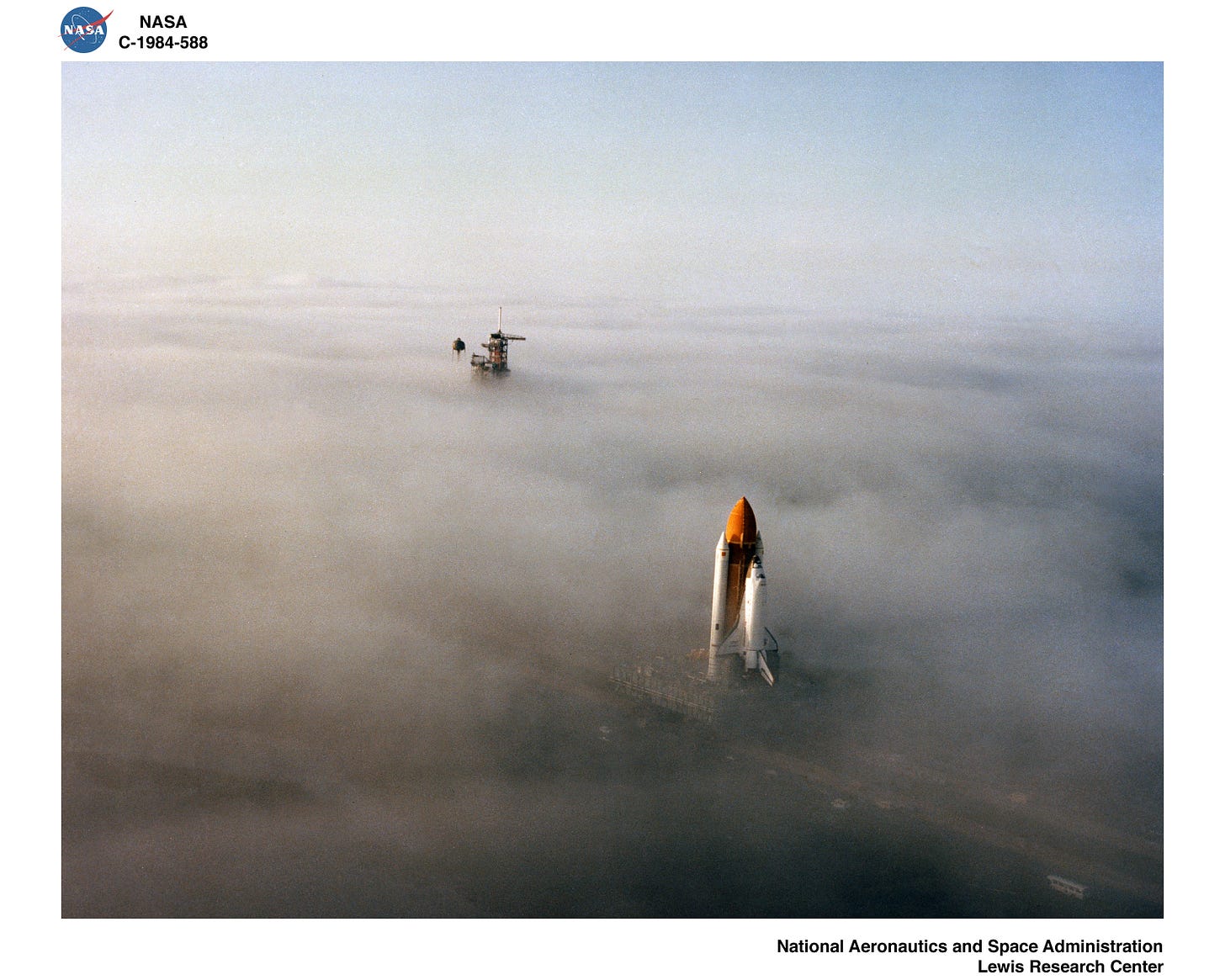

On January 28, 1986, at 11:38 AM, the Space Shuttle Challenger blasted off launch pad LC-39B at the Kennedy Space Center for mission STS-51-L. After a lengthy delay due to below-freezing temperatures that morning, the spaceship was heading toward the stars.

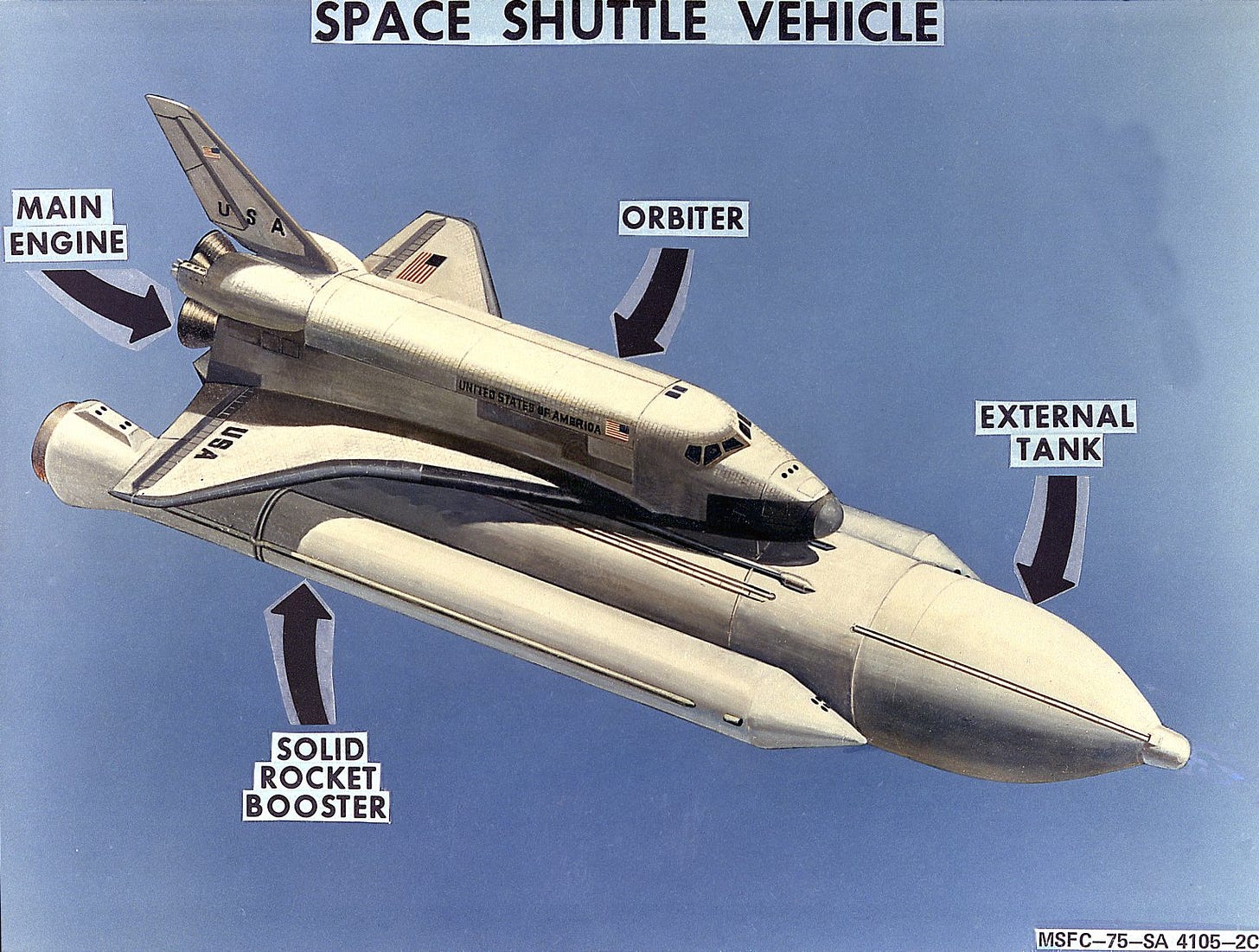

Each Shuttle needed two Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) – the long white rockets stuck to the side of the orange external fuel tank — to attain orbital velocity. The SRBs had four sections sealed together with O-rings. These O-rings prevented the burning fuel exhaust from leaking out the SRB and damaging the rest of the Shuttle stack. Since 1977, four years before the first flight of the Shuttle, NASA engineers had known cold weather, like that on the morning of the 28th, made the O-rings brittle, reducing their ability to create a seal. Despite protests from the SRB engineers and with the Reagan administration’s push for an aggressive launch schedule, NASA proceeded.

One-fourth of a second after the SRBs ignited, the O-rings in the right booster failed. Engineering cameras on the pad detected puffs of smoke shooting out the sides of the SRB as burning fuel pushed against the joints of the rocket.

Within a few seconds, a plug of solid fuel had melted and reformed around the deteriorating joint, briefly recreating a seal and stopping the flames. Challenger climbed off the pad, executed its roll program, and started to ascend to space, complimented by thrilled cheers from the crew.

Forty seconds after launch, as Challenger reached Mach 1 at 19,000 feet, the fuel plug dislodged. Five seconds later, ground cameras showed flames near the right wing as burning rocket fuel escaped from the SRBs. At fifty-nine seconds, the flashes of flame turned into a continually burning plume. Rocket exhaust, which should have been exiting the bottom of the SRBs, was now shooting toward the rest of the spaceship.

Five seconds later the flame began burning through the orange external tank, threatening to ignite the 230,000 pounds of liquid rocket fuel at once. The shuttle was breaking up. Aerodynamic forces mounted as the shuttle deviated from its expected loads. The tank caught on fire and the two rocket boosters yawed side-to-side as their support struts disintegrated. At 73 seconds pilot Michael Smith uttered “Uh-oh.”

A split second later Challenger exploded, killing Francis R. "Dick" Scobee, Michael J. Smith, Ellison S. Onizuka, Judith A. Resnik, Ronald E. McNair, Gregory B. Jarvis, and S. Christa McAuliffe.

Any space disaster is heart-wrenching, but STS-51-L was a special mission. As part of a NASA program to get kids interested in spaceflight, they had selected a teacher, Christa McAuliffe, to join the crew. When Challenger broke up, it was witnessed live not only by spectators at LC-39B — including McAullife’s husband and Peter Billingsly — but by millions of students around the country.

Many things have been said about Challenger, but I haven’t seen it pointed out how many Mormons were connected to the disaster. To be crystal clear: Mormons did not blow up Challenger, but they were very involved in the Shuttle program. Challenger provides a window into this period of history and how members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints found themselves attached to the US government’s high-technology projects — ironic, considering how strongly Mormons hold to antiquated beliefs.

Here are the four connections:

James Fletcher: NASA administrator, champion of the Shuttle project, and SDI theorist

Morton Thoikol: The Utah-based rocket manufacturer that built the Shuttle SRBs

HydraPak: The manufacturers of the fateful O-rings, connected to the FLDS church

Don Lind: Mormon astronaut, flew on a nearly disastrous earlier Challenger mission

James Fletcher

There’s a conventional way to tell the story of early space exploration. This telling hyper-focuses on the US-Soviet race to the moon, and ends at Apollo 11. The United States won, and then all the countries moved on to other projects without the international rivalry, eventually ending up where we are today. Looking at space history this way obscures the second Space Race —this one in the 70s — that saw the superpowers racing to answer the question: “What’s next after the moon?” On the US side, Mormon NASA administrator James Fletcher led the charge.

James Chipman Fletcher comes from an illustrious line of Mormons and scientists. His ancestors converted the church in the early days, leaving Massachusetts, settling with Joseph Smith on the frontier, and following Brigham Young to Utah. Fletcher’s dad, Harvey Fletcher, was a renowned scientist — a key figure in the development of electronic sound and collaborator with Nobel prize winner Robert Millikin. Fletcher was destined for high technology.

After completing his education career in the 40s, Fletcher joined Hughes Aircraft. He’s one of many Mormons who ended up in the Hughes circle.

At Hughes, Fletcher started on the F-102 fighter project. Facing the specter of Soviet bombers invading American airspace, the US Air Force had commissioned the F-102 as an ultra-fast interceptor. Accurately named the Delta Dagger, the interceptor was on the cutting edge of aviation technology, requiring an advanced electronic suite designed by the Hughes corporation. Fletcher also worked on the primary weapon of the F-102, the AIM-4 Falcon missile, getting his first taste of rocketry. Ultimately, the AIM-4 was a dud. Heavily-armed US fighters carried these technological wonders into the skies of Vietnam, only to find them utterly incapable of intercepting enemy aircraft. The Vietnamese pilots easily dodged the missiles, zooming in close to American fighters and blowing them apart with concentrated cannon fire. Only five AIM-4s hit their target during the whole Vietnam War.

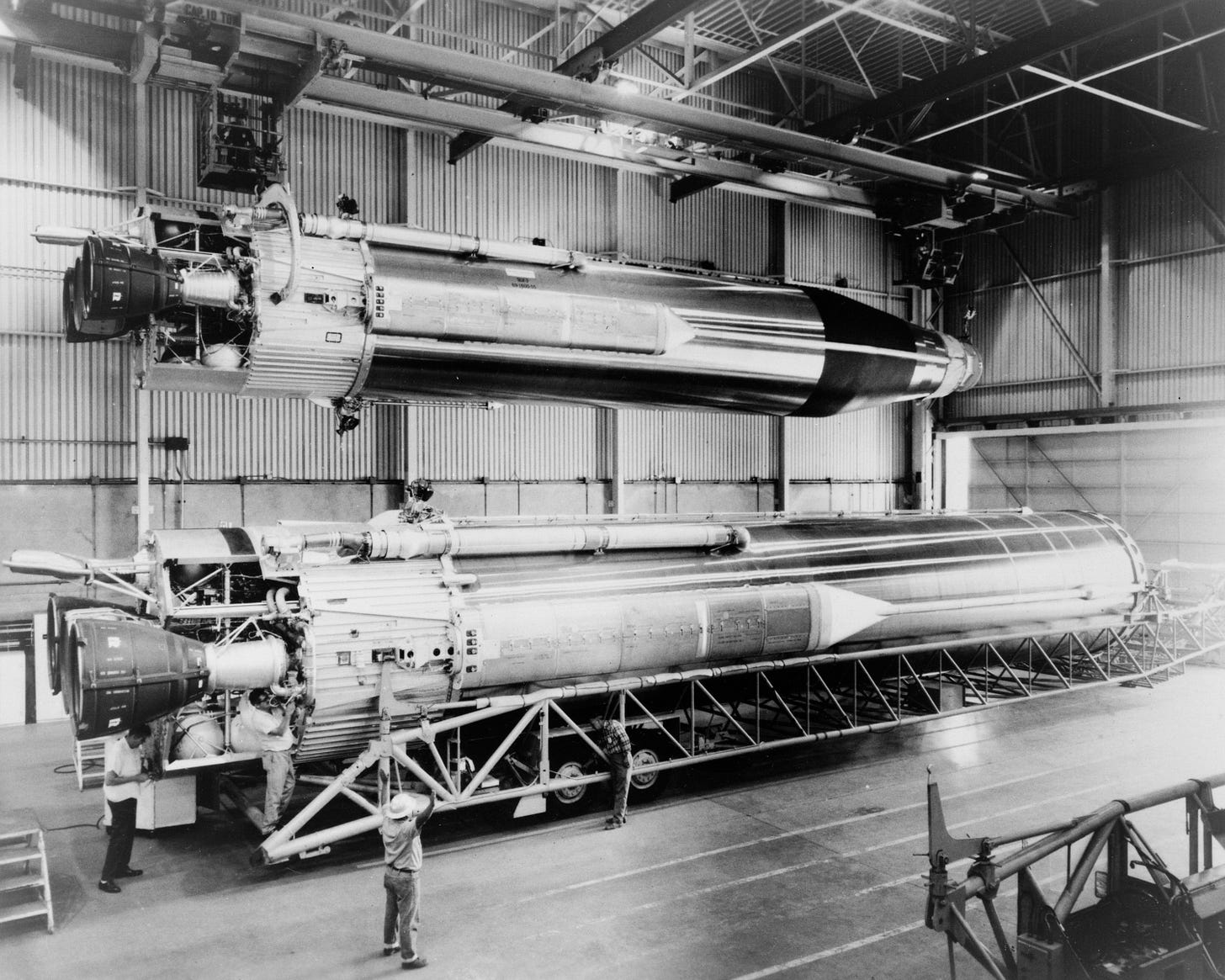

After getting his feet wet in military rocketry, Fletcher joined the Ramo-Wooldridge Corporation, a rival defense company founded by disgruntled Hughes engineers. It was a scary time for the NATO nations. In 1953 the Soviet Union detonated its first hydrogen bomb, spooking the United States into accelerating its ballistic missile development program. With the guidance of polymath John von Neumann, the Ramo-Wooldridge Corporation developed the US’s first intercontinental nuclear missile. Along with the Atlas missile came von Neumann’s theory of mutually assured destruction — an international suicide pact proposing that by stockpiling as many nuclear weapons as possible, the United States would have the power to end life on Earth, thus dissuading the Soviet Union from conducting a nuclear strike against NATO, and vice versa. Fletcher managed the ICBM program and developed system analysis practices for the US missile strategy.

Fletcher’s star was rising within the military-industrial complex. He then joined Aerojet, the rocket engine manufacturer started by occultist Jack Parsons and other CalTech students. After this stint, he worked as president of the University of Utah until Richard Nixon offered him the highest position in United States spaceflight: NASA Administrator.

It was an awkward time for NASA. The Apollo missions had worked (mostly) and defeated the Soviet Union. But what was next? There were a handful of Apollo missions left — these were ambitious, promising to extend Apollo’s capabilities — but the moon was getting stale. NASA couldn’t keep the funding going for a program that the public perceived as being completed with Neil Armstrong’s landing.

Behind the Iron Curtain, the Soviet engineers were pondering similar questions. They had lost the race to the moon, only accomplishing uncrewed circumlunar flights. Vasily Mishin’s massive N1 rocket (the Soviet equivalent to the Saturn V) had never successfully flown. The backup design — Vladimir Chelomey’s UR-700 — never left the drawing board. However, the Soviets had another program up their sleeve. In the early 60s, after learning that the US Air Force was building a military space station based on the Gemini spacecraft, Soviet leadership started the DOS program, a project to build an inhabited orbital space station, the first in the world. If they had lost the race to the moon, the Soviets wouldn’t lose the race to have man live among the stars.

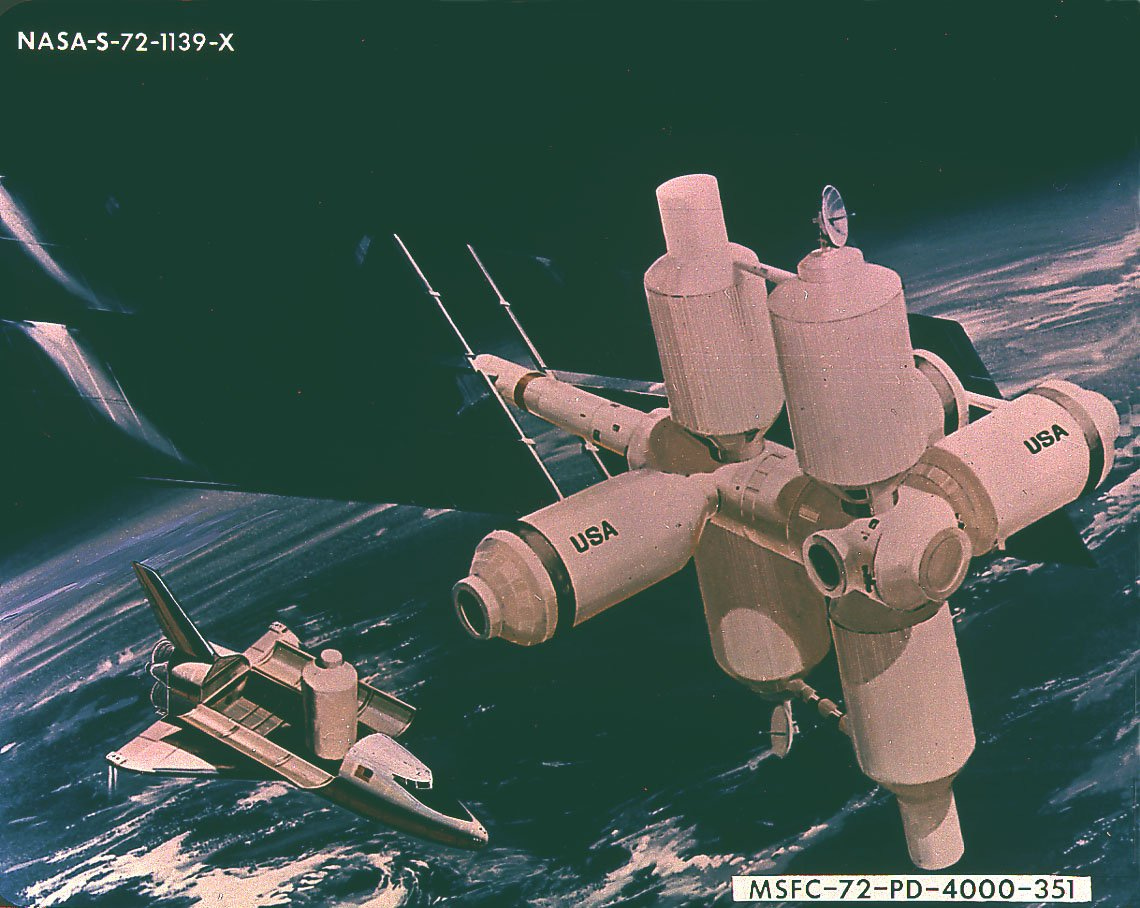

The Americans were looking for a new flagship program to show that the Apollo missions weren’t a one-and-done thing for NASA but rather the start of American space exploration supremacy. The Saturn rockets and the Apollo CSM stack worked, so Fletcher and NASA started the Apollo Applications Program (AAP) to study proposals for reusing these components for new missions. The AAP spawned dozens of plans, including a manned Venus mission, but in the end, two prevailed. Skylab would be America’s first space station, made from a reused Saturn V third stage. To accompany Nixon’s détente foreign policy, NASA also planned the first international orbital docking using an Apollo capsule and a Soviet Soyuz ship. We’ll talk more about these two projects below because Fletcher’s biggest project leapfrogged AAP.

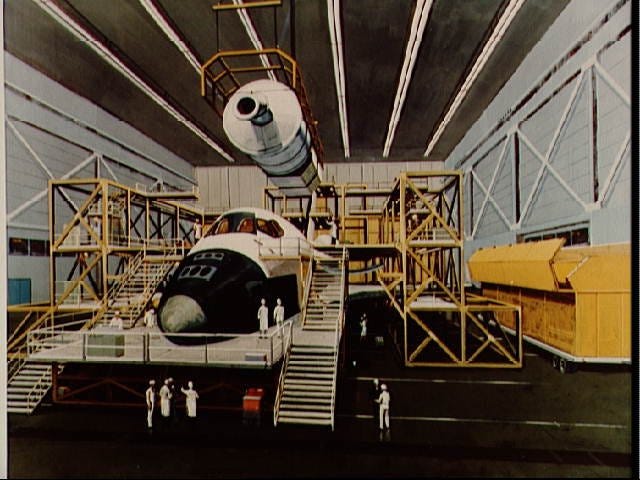

Low-cost, reusable spaceflight is the holy grail for rocket scientists. That’s the science fiction dream — being able to take a rocket flight as easily as you would take an airplane to a different city. The Apollo program, as impressive as it was, definitely was not low-cost, nor reusable. The capsules were ruined after re-entry, and the whole mission was anything but simple. NASA had many ideas for reusable spaceflight, but in the end, they settled on a hybrid space plane that could launch into space, land like an airplane, and turn around to do it again within a short time frame. A Space Shuttle.

NASA understood that emphasizing economic considerations was the best way to sell the vehicle. George Mueller, one of the biggest Shuttle enthusiasts, estimated that such a vehicle could reduce launch costs from $1,000 per pound to as low as $25 per pound. Nixon liked the finances, but really liked having a flagship NASA program attached to his name that wasn’t started by his archrival JFK. The Nixon administration didn’t want more of these flashy Apollo-style programs — they wanted something well-organized, in-line with Nixon’s policy goals, and with streamlined management to reduce organizational costs. Of course, the United States military was interested in the Shuttle too, seeing it as an easy way to deploy military spacecraft to fight the Soviets. Fletcher had a lot he needed to do.

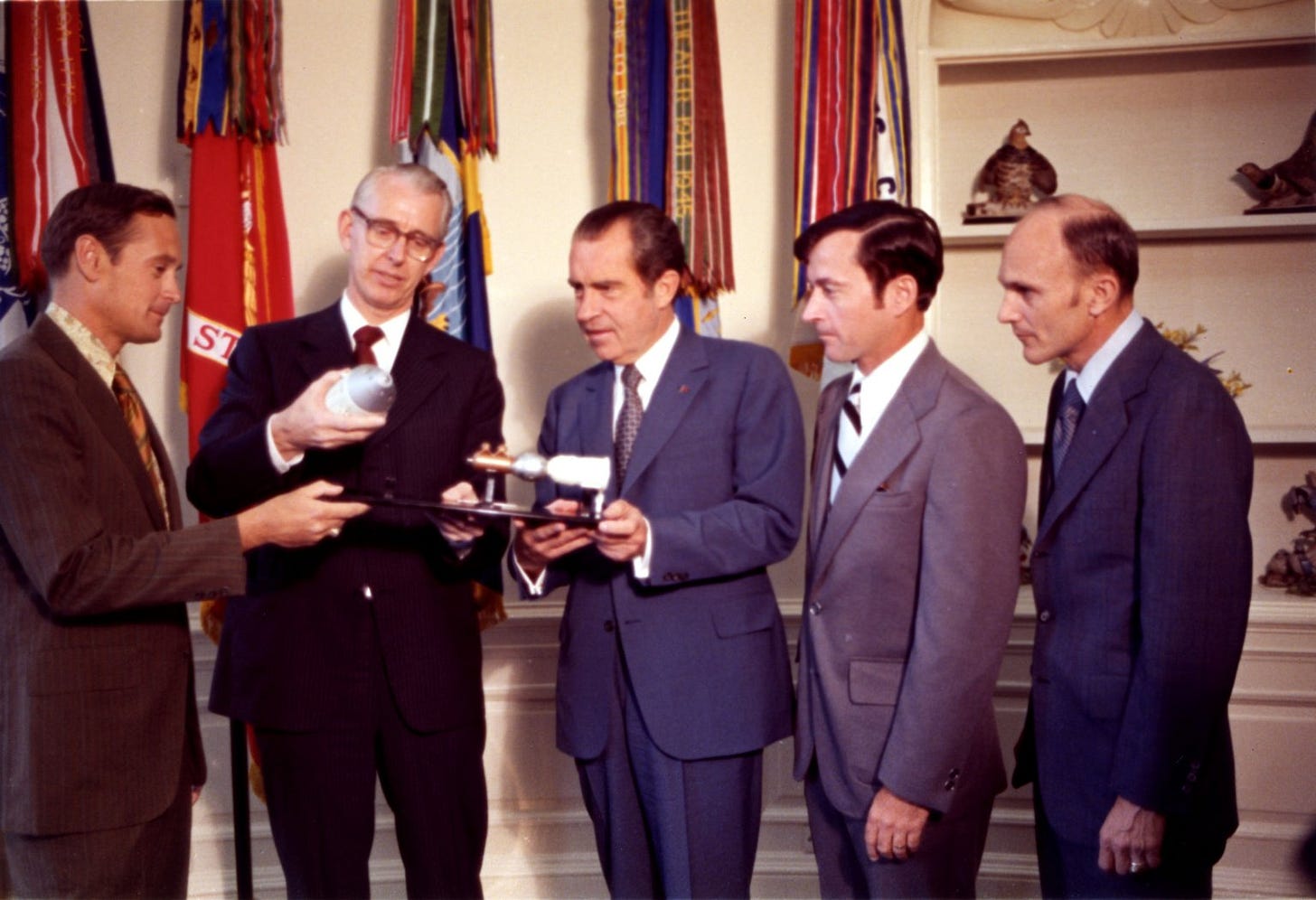

Space Shuttle concepts were flying off the drawing board by the early 70s. Seemingly every aerospace engineer in the country had a proposal. Many dovetailed with NASA’s goals of building an orbiting space station to compete with the Soviet DOS program. The Shuttle, in its mature form, could cheaply ferry astronauts and equipment to and from a future station. With cost such a sticking point, Fletcher worked to reign in the more outlandish proposals, clarify the goals of the program, and develop a launch architecture. By 1971 he settled on a delta-winged orbiter boosted into space by two rockets attached to an external fuel tank. The contract for these rockets, the Solid Rocket Boosters, went to Utah company Morton Thiokol, old friends from his Aerojet days.

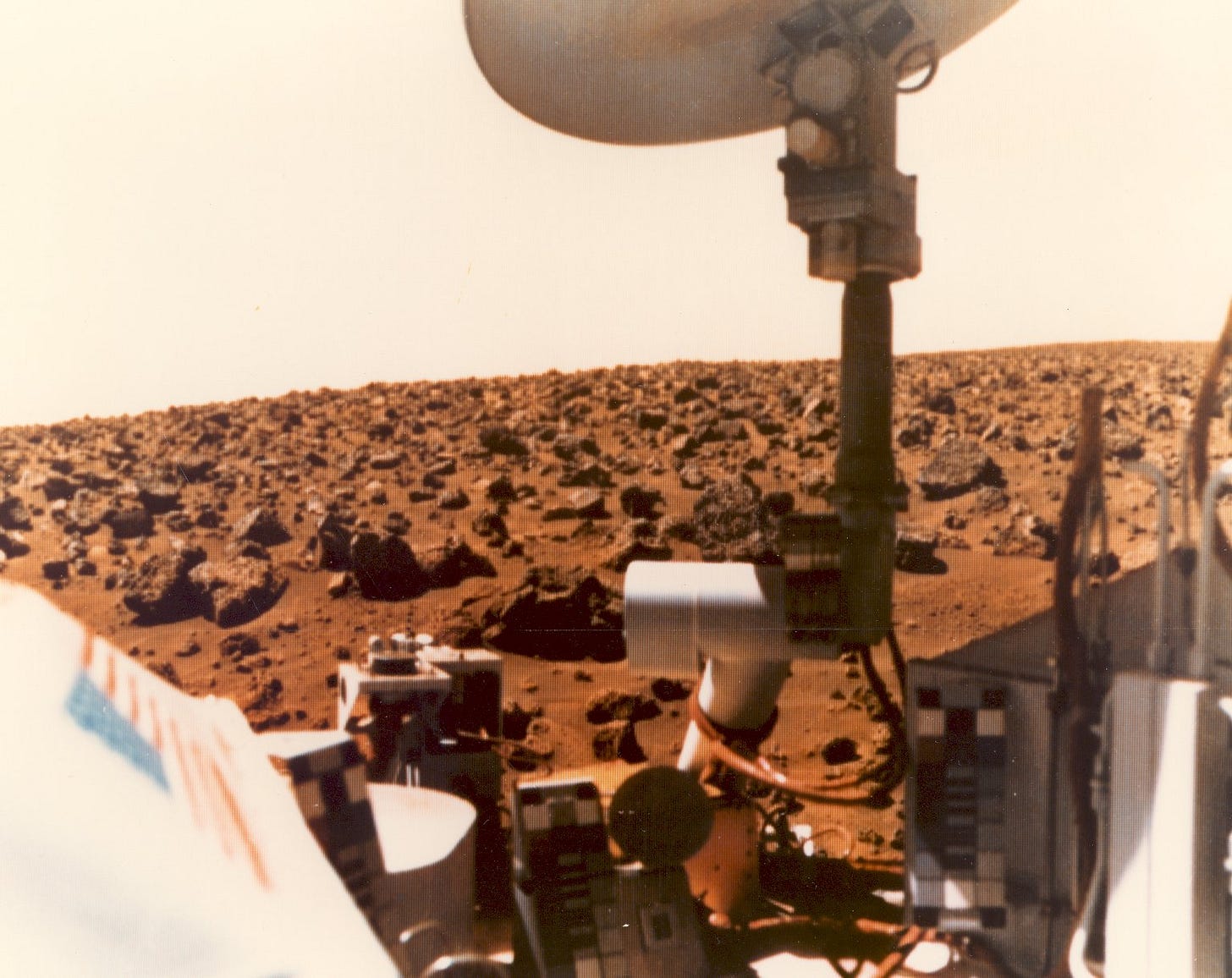

The political football is a little too deep for the scope of this article, but suffice it to say, the Space Shuttle program endured a massive fight before Nixon signed off on it in 1973. James Fletcher ended his Administratorship in 1977, having overseen the Skylab missions, the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, three Apollo moon landings, two successful robotic landings on Mars, and got the Space Shuttle into development. Mostly, his career was successful, although the Soviets had beat the Americans in putting up the first space station. But Fletcher’s time with NASA wasn’t over.

Before he reentered NASA service, Fletcher went back to doing what he was doing before: using space technologies to endanger the human race. Both sides of the Cold War realized that space would become a key battle zone in a hypothetical World War III. The Space Shuttle was designed, under Fletcher, with the military intimately involved. Even during peacetime, the Space Shuttle flew classified Department of Defense payloads, like on STS-36.

In the spending bonanza following Ronald Reagan’s election, new military toys were all the rage. In 1984 he organized the Strategic Defense Initiative, also called the Star Wars program by its critics. The SDI funded exotic space-based weaponry, ostensibly to provide a defensive grid against Soviet nuclear missiles. SDI planners imagined an arsenal of technological terrors — laser-carrying satellites, spacecraft that would launch anti-satellite missiles, spinning fan-bladed rockets that could intercept incoming warheads, and more.

James C. Fletcher was immediately tapped for the new program, as well as a Red Team of scientific advisors that would keep Reagan apprised of Soviet weapon development. Besides the funding issues (which were exorbitant), SDI had a terrifying philosophical implication. It threatened to kick off a new offensive arms-race, this time with insanely destructive space weapons. Polish author Stanislaw Lem prophetically warned against this in his 1967 novel His Master’s Voice:

The [political] situation has been complicated in a new way by a ‘mirror pas de deux,’ since one side of the world has been obliged to copy, as accurately and as rapidly as possible, everything that has been done by the other in the field of armaments. And often it is impossible to tell who takes a certain step first, and who merely imitates it faithfully… the state of equilibrium is continually being undermined by new discoveries and inventions… The competition-duel in nuclear payloads gave way to a missile race, and that in turn led to the building of more and more expensive ‘antimissile missiles.’

SDI was a trap, locking humanity into another round of military posturing and expanding the Cold War into deep space. Neither Reagan nor his scientists seemed to understand this. Or if they did, they didn’t care.

In 1986, when Challenger blew up, William Robert Graham stepped down from his role as NASA Administrator. Reagan pulled Fletcher out of SDI and installed him as the new Administrator, making Fletcher the only person who has held the office twice.

Reagan immediately ordered a Presidential Commission to investigate the disaster, but off the bat it was politically compromised. Reagan had told Chairman William Rogers that the number one priority of the investigation was to not embarrass NASA. They knew that NASA had fucked up, but the agency was a key player in Reagan’s future space warfare plans.

The Commission started under Fletcher’s watchful eye, staffed with some of the biggest names in spaceflight and physics, such as Neil Armstrong, Sally Ride, Richard Feynman, and Chuck Yeager. Immediately, it became clear that NASA was stonewalling the investigation. However, Feynman and Ride weren’t playing along, leading Rogers to complain to Armstrong — while peeing next to each other at urinals — that "Feynman is becoming a real pain."

Sally Ride, the first US woman in space, and one of my favorite astronauts, leaked documents showing that NASA was well aware of the faults in the O-rings. Feynman, in a characteristically theatrical fashion, demonstrated the danger of freezing temperatures, a problem that NASA had been covering up since before the Shuttle had even flown. Worse still, NASA had purposefully misrepresented the safety margins on STS-51-L to convince Christie McAuliffe to fly.

With NASA’s cover blown, Fletcher ordered a complete reworking of the Shuttle program, including redesigning the Solid Rocket Boosters. The Space Shuttle returned to flight on September 29, 1988, and Fletcher spent the rest of his administration setting the groundwork for the Hubble Space Telescope. He stepped down in 1989 and died two years later, a faithful Mormon to the end.

James C. Fletcher was a living example of the dichotomy of manned spaceflight. Fletcher brought about one of the biggest expansions in NASA, overseeing some of the best missions they ever ran. On the other hand, he had cut his teeth on ICBMs and went right back to military spaceflight after leaving NASA. That’s how spaceflight has always been — the same tools that let us explore our universe are also the tools that can end the human race. Fletcher was a key figure in both.

Morton Thiokol

The Rogers Commission ultimately placed the blame for the disaster on NASA and Morton Thiokol, the builders of the Shuttle’s Solid Rocket Boosters. Remember, these are the white rockets attached to the side of the orange external tank. They provided the extra thrust needed to get the Shuttle into space and used solid rocket fuel instead of liquid fuel — thus the name.

Morton Thiokol has gone through many incarnations and many names throughout its history (you’ll see this iteration of them with or without a hyphen.) Mostly they build weapons.

They got into the world of rocketry after World War II. Occultist Jack Parsons and fellow CalTech students were developing rocket boosters for Air Force aircraft and Morton Thiokol jumped in to improve the students’ solid rocket fuel. Ultimately, the CalTech students formed the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Aerojet, moving on to liquid-fueled rockets, but Morton Thiokol stayed with solid propellants. These have some key advantages over liquid rocket fuel. They can deliver a lot of thrust, very quickly. They are cheap. Most importantly, solid propellants can sit inside a rocket for a long time without the fuel quality degrading. That means a rocket can get loaded up and sit around, ready to fly at a moment’s notice. Perfect for nuclear missiles.

In the 1950s, Morton Thiokol picked up contracts to build the first generation of American ICBMs. They needed lots of room to test rockets away from the public eye, and Utah was the place. The Air Force had long used the open desert landscape for weapons tests, including training the B-29 crews that dropped The Bomb over Japan and testing prototype A-12 spy planes. Morton Thiokol set up shop in Brigham City, Utah, and started building rockets.

The rocket builder transformed this small Mormon town, providing steady jobs and an influx of government funds. Employees were almost exclusively native Utahns — the company found it nearly impossible to convince people to move to backwater Utah, especially because the few rocket transplants (often coming with their own religious beliefs) were instantly hit with conversion efforts:

We found that a lot of these people that came in were non-Mormons and they were a little fearful of coming into a Mormon community. We just bent over backwards to do anything that we could to do away with that thing. We tried to be friendly, overfriendly, if possible, to make them feel at home here. Then we had a number of people trying to convert them, and they resented it sometimes because they felt that they were already converted. They didn’t want their lives interfered with.

James C. Fletcher gave Morton Thiokol the contract to build the Space Shuttle’s Solid Rocket Boosters, providing more jobs to Utah’s rapidly militarizing economy. Building and testing started, but by 1977, before the Space Shuttle was even launched, they realized that the SRBs were woefully unsafe. Specifically, the issue was with the O-rings. Morton Thiokol explained this to NASA, but both parties decided not to delay the project to iron out the kinks.

While the design of the SRBs was fundamentally unsafe, Morton Thiokol was actively making the situation worse. A culture of lax safety procedures permeated the company. In 1971 their magnesium flare plant exploded, killing 29 people. An inspection of an SRB assembly plant revealed that:

In a subcontractor's assembly plant, inspectors found workers storing their lunches in refrigerators alongside strips of rubber used to manufacture the crucial seals. Workers were also found to be using paint marks on the floor to measure the O-rings. And in one Morton-Thiokol plant, an Air Force inspector discovered that new and used O-rings were stored in the same area. In his report, he speculated on the ‘possibility of intermixing’ them during the assembly of the rocket boosters.

The company managers also routinely ignored concerns brought by engineers. Six months before STS-51-L, an engineer recommended ceasing all shuttle flights until they fixed the problems with the O-rings. Management ignored them. The day before the Challenger disaster 15 Morton Thiokol engineers demanded that the shuttle not be launched. They were overruled. That night engineer Bob Ebeling told his wife "It's going to blow up." For 30 years Ebeling blamed himself for the deaths. It wasn’t his fault. He had done all he could have done.

Immediately after the disaster, Morton Thiokol and Brigham City circled the wagons. Mayor Peter C. Knudson moaned to the press:

We had 24 successful launches and nobody noticed. Now that a tragedy occurs, the people are paying attention to us. We have this kangaroo court that judges Morton Thiokol guilty. It's not fair. It's not just.

By the way, this guy is still around, and represents the 17th District in the Utah State Senate. He also said this, which kind of sounds like he’s alleging that criticism of Morton Thiokol also constituted anti-Mormon rhetoric:

About 80 percent of the residents are Mormons, Mayor Knudson estimated. That fact, he said, made it especially hard for local residents to bear a nation's collective suspicion that because they did not do a good job, seven people had died in the explosion.

You're going to be hard pressed to find more dedicated people than they have here. I'm not saying there aren't good people elsewhere, but there is a work ethic here that's hard to duplicate. They are No. 1, family people; next they are dedicated to their work. We are not dealing with a bunch of 9-to-5 schlocks who forget the job when they go home.

Hey, don’t worry dude. NASA gave Morton Thiokol a $10 million fine but also turned around and gave them a $75 million contract. The company split up, with Thiokol taking the spaceflight contracts. They continued to build SRBs for the Space Shuttle and still build stuff for NASA, along with rocket motors for missiles, ICBMs, and other weapons. Key examples of their products are on display in a park 25 miles away from Brigham City.

So what about the O-rings themselves? Well …

HydraPak

The mainline Mormon church often gets most of the attention for their vast business holdings, but their smaller cousins — the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints — also have their money-making enterprises. This is the polygamist outfit run by Warren Jeffs. With so many wives and so many babies getting made, the FLDS have a captive labor pool.

Up and down the Western United States, the FLDS run their enterprises. You’ve probably run into an FLDS business if you live out there, you just didn’t know it. One of these businesses is HydraPak (alternatively Western Precision or NewEra Manufacturing.) The company was founded by Warren Jeffs and run by Wallace Jeffs. If you’ve seen the documentary Keep Sweet, Pray, and Obey, Wallace is in it. He’s since left the FLDS and joined the mainline LDS church. The FLDS tried to kill him.

But back in the 80s, his company was awarded the sole contract to build the O-rings that would go in Space Shuttle SRBs. The FLDS would have their adherents build the O-rings and then ship them off to Morton Thiokol.

Immediately after the Challenger explosion, an FBI investigation revealed that some of the O-rings had been sabotaged at the HydraPak plant before being delivered to Morton Thiokol. Both companies denied that the sabotaged O-rings had never made it into the SRBs. But Morton Thiokol employees told investigators they had seen the sabotaged O-rings being loaded into the boosters. NASA had nothing to say about that. Morton Thiokol’s lax safety culture doesn’t exactly instill confidence that Challenger wasn’t using the sabotaged O-rings.

HydraPak conducted an internal investigation and said they couldn’t find who did it, but more slashed O-rings kept cropping up. It seems like NASA and the FBI just took HydraPak’s word because I can’t find any follow-up to this.

Chances the FLDS slave labor built fine O-rings — NASA and Morton Thiokol didn’t use them correctly.

Anyways, let’s see what HydraPak’s up to now…

Don Lind

As a dedicated space nerd, I’m always hesitant to criticize astronauts. They almost feel sacred, like by flying into space they also escape criticism. But man, does Don Lind come off like a massive dickhead.

Lind has the dubious honor of taking the longest time from getting accepted as an astronaut to flying into space — 19 years. Bad luck maybe, but once you start digging into his story, it looks more like he sabotaged himself.

Lind was accepted into NASA Astronaut Group 5. Man, if it wasn’t a badass group of astronauts. You’ve got Fred Haise and Jack Swigert, two crew members on Apollo 13, as well as Ken Mattingly, the astronaut who got bumped from the crew for rubella but flew on Apollo 16. Then you have Jim Irwin, the guy who probably brought the Utah flag to the moon that trolled Joseph Fielding Smith. Bruce McCandless II was in this group. He took a long time to get to space, but once he did, he did an EVA untethered, posing for some of the coolest pictures in spaceflight history. And who could forget Charlie Duke, LMP for Apollo 16 and the iconic CAPCOM for the Apollo 11 landing: “Roger, Tranquility. We copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.”

Then you have Don Lind.

When Lind joined up, NASA was investigating sending trained scientists to the moon. The first few flights had been done by military pilots, but for the upcoming “J - Type” missions NASA wanted to focus on science. They souped-up the lunar lander and gave it a sweet Lunar Rover to let the new scientist-astronauts cruise around the Moon’s surface.

Lind worked his way into the astronaut roster and would have flown on either Apollo 18, 19, or 20. He helped develop the scientific experiments carried out on Apollo 11 and served as a CAPCOM for both that mission and Apollo 12. But his flight to the moon wasn’t in the cards. By the late-60s, Chief Astronaut Deke Slayton could see that funding wouldn’t last for the later missions, and he wouldn’t have had a flight for Lind.

Slayton moved Lind over to the Apollo Applications Program. Lind didn’t take this setback gracefully and began openly complaining about perceived favoritism among the astronaut corps, criticizing Slayton’s managerial decisions. When the managers didn’t respond to his complaints, he went to the press.

This didn’t enamor him with NASA management, but fortunately for Lind, the second space race was heating up. The Soviets, licking their wounds from losing the race to the moon, focused on its DOS space station program. The program would have two parts, a civilian and military side, although they were so mixed together organizationally that it was hard to tell which was which. While the Soviet moon program was failing to successfully launch even one N-1 rocket, DOS had been slowly ticking along.

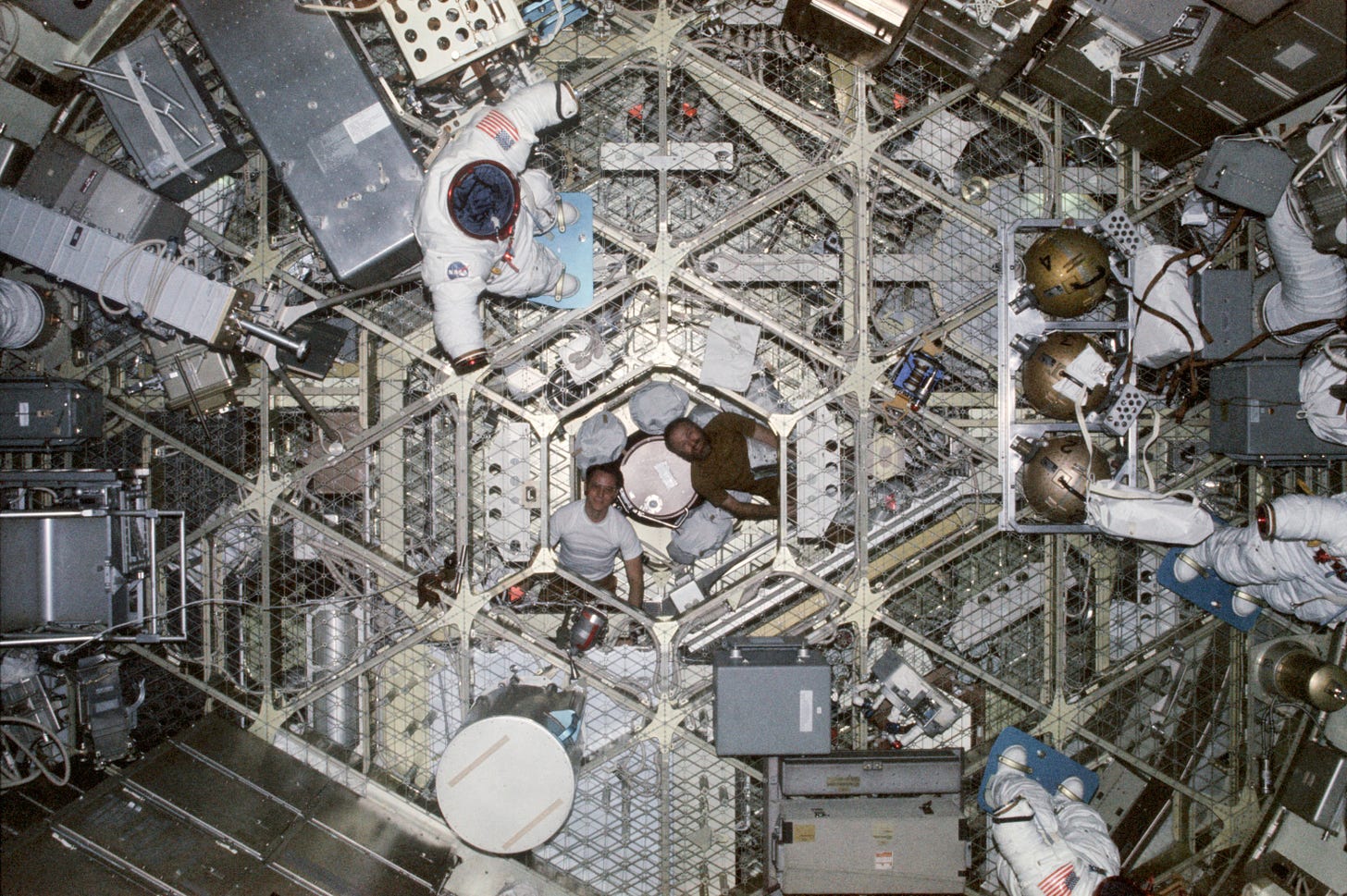

NASA, not wanting to lag behind their Soviet counterparts, fast-tracked Skylab, a space station based on existing Apollo hardware. The station proper would be a modified S-IVB stage of the Saturn rocket, fitted out with everything the astronauts would need to live in space. The Apollo CSM stack (the command module and service module, sans lunar lander) would carry the astronauts to the station. NASA began training its astronauts, including Don Lind, for this next step into the frontier.

The Soviets would win this race. On April 19, 1971 the first human space station, Salyut 1, rocketed into orbit. The first crew wasn’t able to dock, but the next one — Soyuz 11 — successfully docked and worked in the station. The mission, however, ended in disaster. During reentry, a valve erroneously opened, depressurizing the Soyuz spacecraft and killing Georgy Dobrovolsky, Vladislav Volkov, and Viktor Patsayev.

By this time, Don Lind had been moved to a backup crew for Skylab, much to his chagrin. He told NASA officials that he was hoping that the prime crews would get their legs broken before their flight. Hey, maybe don’t complain about your boss to The Washington Post? He was still given a cool position though. Not only was he part of the backup crew, but he was also training for the Skylab Rescue Mission, an emergency mission designed to rescue the astronauts if they got stranded on the station.

In 1973 Skylab was ready for launch. The Soviets raced to get their next station, Salyut 2, into orbit before Skylab. This was the first military space station, codenamed Almaz. Salyut 2 obtained orbit on April 3, 1973, but fell apart before crews could inhabit it. On May 5, 1973, Skylab launched. Two weeks later, the first crew, Skylab 2, entered the station.

A lot of things went wrong during the three Skylab missions, including an onboard mutiny, but none of them were bad enough to have Lind fly. He got pretty close though. The Skylab 3 crew lost one of its four reaction control systems during the approach to the station. Shortly thereafter, a second RCS system sprung a leak. It was unclear if they could deorbit with only half their RCS thrusters, so Don Lind’s backup capsule was integrated and rolled out onto the pad. This would have been Lind’s chance, but the crew figured out a way to deorbit safely. CSM-119 was rolled back into the Vehicular Assembly Building and is now on display at the NASA Kennedy Space Center.

(AUTHOR’S NOTE 5/12/2023: I watched Scott Manley’s video on the Skylab Rescue Mission and felt like I unfairly undersold Lind’s contribution to getting Skylab 3 back home. Him and Vance Brand worked hard to develop a procedure for maneuvering with only 2 RCS systems, and did this so effectively that they ended up developing a plan to get the CSM back home without any RCS thrusters working on the Service Module. Lind did such a good job he made his own flight unnecessary.)

Lind was assigned to Skylab 5, which got canceled. Now getting increasingly disgruntled, Lind joined the Space Shuttle program. Finally, in 1985 he was assigned to STS-51-B, flying into space on the Challenger.

This is where Don Lind gets really dickish. After Challenger landed, Lind was talking to the engineers at Morton Thiokol. They told him that the O-rings on his mission had almost failed in flight, the same way that they failed on STS-51-L. “You came within three-tenths of one second of dying."

That’s enough to shake anybody, and I don’t begrudge him for finding solace in his faith. I find the way he reacted to this news very distasteful though. From his oral history:

We thought that was significant in our family. I painted a picture of our liftoff. Our son [was] is the photo editor of the Daily Universe, which is the student newspaper at Brigham Young University [Provo, Utah]. I [had gotten] him press credentials, [and] he took some really professional-type pictures of our liftoff.

So I painted a picture of our liftoff. The steam is rolling up in exactly the right pattern and everything. Then I painted two great celestial hands supporting the Shuttle, and the title of that picture is Three-tenths of a Second. Each of our seven children have in their home a copy of that painting, because we wanted the grandchildren to know that we think the Lord really protected Grandpa.

I mean, that’s cool that Mormon Jesus protected Don Lind, but why didn’t he protect the crew of STS-51-L? Why did he let a random school teacher, somebody who shouldn’t have been on the flight, die? Why did Don Lind think he was so special?

It seems like Lind himself realized that this sort of talk was pretty gross, so he tried to soften the blow when he talked to LDS Living.

Lind believes that a priesthood blessing he received before his flight protected him and his crew from a similar fate as they hurtled through the earth’s atmosphere aboard that very space shuttle. Full of faith and gratitude for the Lord’s protection, Lind said, “We weren’t more righteous or more deserving of the Lord’s help—those on the Challenger were good people—but it had been promised us.”

Honestly, that might be worse! Oh, if only the crew of STS-51-L had had a Mormon man promise them that they would survive. Good for Lind that he had this special power at his disposal, a power that is denied to Mormon women and used to be denied to people of color.

Don Lind was given the honor of speaking at the 1985 General Conference, one of the few non-General Authorities in Mormon history to do so. He awkwardly recounted discretely taking the sacrament in space and told the young men that he was only able to pass the astronaut physicals because he obeyed the Word of Wisdom dietary restrictions. Lind also told NASA officials this during his oral history. You might be thinking: “Wait, but most astronauts didn’t obey this, and they all became astronauts, and Don Lind was always back up to them.” Well… yeah…

Don Lind died in 2022, having lived a full life that his God didn’t give Francis R. "Dick" Scobee, Michael J. Smith, Ellison S. Onizuka, Judith A. Resnik, Ronald E. McNair, Gregory B. Jarvis, and S. Christa McAuliffe.