The Department of Defense Connection to the Missionary Training Center

The Missionary Training Center — a tightly packed campus neighboring BYU-Provo, filled with identical dorm buildings and covered sidewalk pathways, surrounded by a fence and guard box — is the first stop for a Mormon missionary. It’s a crash course in strict obedience to the mission rules and effective deployment of the church’s high-pressure recruitment tactics. Most missionaries will learn a new language.

Teaching a fresh high school graduate a foreign language isn’t easy in the best-case scenario, and the MTC is in a time crunch. Missionaries are only in the MTC for a few weeks. Since they can’t waste a day in the field, they’ll need to learn a language well enough to start converting people on Day 1 in a foreign country.

The Mormon missionary language program needs every advantage it can get. To help ensure success, the Mormons in the 1970s employed cutting-edge linguistic research and state-of-the-art computer systems.

Also, some Department of Defense cash.

Machine Linguistics

In the 50s and 60s, three currents changed linguistics: Noam Chomsky’s work at MIT, next-generation computers promising increased computational speed, and the US’s need to quickly teach government agents the languages they’d need for intelligence operations.

Automatic machine translation research (using computers to translate between languages) kicked off almost immediately after the invention of ENIAC. The US funded university computer programs across the country, focusing on translations between Russian and English. The Cold War was heating up. As US letter agents traveled the world, automatic translation provided a prospective espionage advantage.

However, despite promising starts, machine translation made little headway. By 1964 it looked like a dead end, despite a new generation of computers coming online. Congress convened the Automatic Language Processing Advisory Committee (ALPAC) to analyze the research progress. The committee found that automatic machine translation was unachievable in the near future, recommending a drastic funding cut.

Simultaneously, a linguistic revolution took place at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Firebrand linguist Noam Chomsky was the face of a new linguistic generation, fighting to restructure how we understand language and kicking off an academic conflict.

Out West, despite the ALPAC report’s dismal forecasting, Brigham Young University soldiered on, funding machine translation to fulfill Joseph Smith’s prophecy that “every man shall hear the fulness [sic] of the gospel in his own tongue, and in his own language.”

Dr. Eldon Lytle

Enter linguist Dr. Eldon Lytle.

After receiving a master’s degree from BYU, the young linguist studied at the University of Illinois (Champaign-Urbana), graduating in 1971 with his dissertation, “Structural Derivation in Russian.”

Dr. Lytle’s dissertation proposed junction grammar as an alternate approach to Chomsky’s transformational grammar. Lytle is unambiguous in his recollection: his work directly opposed “Chomsky’s gospel.” From his own origin story on http://www.junction-grammar.com/html/origins.html :

The 1960’s were, to say the least, an era of national hand-wringing and personal conflict in the United States. Not only was the war in South Vietnam running its deadly course but the war in linguistics was heating up. The latter conflagration, while perhaps not making headlines, was pernicious and deadly in its own right. Linguistic science on the American scene had been assaulted and overrun by the warriors of the so-called Chomskian revolution.

As a grad student working towards a Ph.D. in Slavic Languages and Literature at the University of Illinois (Champaign-Urbana), my first exposure to the ‘new linguistics’ occurred in the fall of 1966. Several of Chomsky’s protégés were practicing their craft in the linguistics department there at that time. They were supremely confident in the proposition that no plausible alternatives to Transformational Grammar could possibly exist. Not content to peddle their own wares, some set about to publicly attack and discredit the work of any and all not subscribing to Chomsky’s gospel.

The Linguistic Society of America under Chomsky’s influence had not only squelched alternative views but actively supported the anti-war movement of the 60’s. The exodus of LSA members in the wake of these indiscretions eventually gave rise to the Linguistic Society of Canada and the United States (LACUS), which, under the watch care of Adam Makkai and his colleagues, steered clear of political entanglements and provided a friendly, open forum for the free flow of ideas and discussion.

According to Dr. Lytle, junction grammar is an alternative approach to Chomsky’s:

In sidelining semantics, Chomsky had set up the syntactic component as the generative base and assigned to semantics an interpretive role. [Junction Grammar] turned them the other way, making semantics generative and syntax interpretive.

Junction grammar’s exact details are beyond this article’s scope, but curious readers are encouraged to look through Dr. Lytle’s website.

To me, the two salient points about junction grammar are as follows:

Dr. Lytle invented his theories as both a direct inversion of Chomsky’s and a refutation of Chomsky’s political goals. Dr. Lytle perceived Chomsky’s linguistic work as connecting to the anti-war movement and a broader left-wing political program. In a sense, he formulated his linguistic theories as a politically safer alternative to Chomsky, allowing potential clients to get involved in linguistic research without anti-war intrigue.

Dr. Lytle viewed his work as a revolution, founded on biological certainty: “JG can do for linguistics what the Periodic Chart of Elements did for chemistry and Schrödinger’s equation did for physics.” In selling his theories, he wasn’t simply offering a new way to learn, he was offering a silver bullet that would give any interested party an unquestioned linguistic edge.

BYU’s Linguistic Research

Brigham Young University was eager to start a new linguistic revolution. Plus, they had some applications already in mind.

Under BYU’s auspices, Dr. Lytle founded the Automated Language Processing (ALP) group, applying junction grammar to computer-aided translation research. Eventually, the ALP group got folded into BYU’s Translation Sciences Institute (TSI). According to church magazine articles from the 70s, the TSI’s primary goal was finding a quicker way to translate the Book of Mormon into different languages.

But, Dr. Lytle needed to test his theories, and the Mormon missionary program was just the place. As Mormon missionaries prepared to enter the mission field, they needed to rapidly learn foreign languages, maximizing the time they could spend converting prospective members.

To this end, the Mormon church founded the Language Training Mission (LTM), a foreign language missionary boot camp. They wanted Dr. Lytle to develop the language-learning curriculum.

The Mormon church was not the only party interested in Dr. Lytle’s work. The Department of Defense and Central Intelligence Agency, despite the ALPAC report, considered machine translation an advantage they could gain over their Eastern Bloc rivals. The BYU ALP group was just the ticket, mixing cutting-edge linguistics with computer automation and a burning sense of American patriotism.

The funding began.

And thus, the link was forged, through Dr. Lytle, between the Department of Defense and the fledgling standardized Mormon missionary program with its guinea pigs at the LTM, soon to be renamed the Missionary Training Center.

Department of Defense Funding

When you look for Mormon and Department of Defense connections, you are trying to pry information from two extremely secretive organizations. I wish I had a smoking gun to give you, a receipt, or direct confirmation. But here’s what I have.

The best reference comes from The Mormon Corporate Empire. Despite being written by a fundamentalist Mormon alternative medicine quack and a sociologist affiliated with Scientology, the book has good references for Mormon/DoD connections.

They reported, based on a conversation with ALP researcher Mike Hannon, that the ALP group (later known as Automatic Language Processing Systems Inc.) received military funding to develop automatic computer-aided translation software. The goal, it seems, was to rapidly translate Eastern Bloc technical documents and intelligence. Hannon estimated that the CIA and military fronted 20-30% of ALPS’s funding.

According to “‘The Need Beyond Reason’ and Other Essays,” published in 1976, the ALP group received at least two contracts from the Department of Defense. This book is hard to come by, and I could only find a Google Snippet view. If you have access to this book, please DM me on Twitter.

The ALP group also shares personnel and funding with the Eyring Research Institute, a shadowy think tank operated by BYU with direct DoD connections. I will be writing much, much more about these people later.

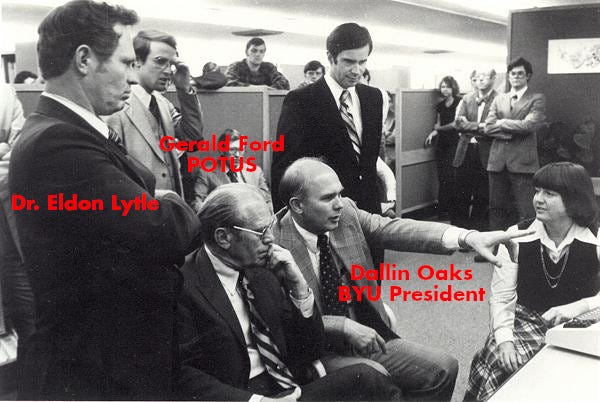

And, weirdly, you have this picture of President Gerald Ford and BYU President Dallin Oaks examining computer translation technology at BYU.

Putting all this together, you have the Department of Defense funding a linguistic program that developed and implemented its pedagogy at the Language Training Mission.

Where is Everybody Now?

Dr. Lytle went on to have a long career, furthering his linguistic experiments through tests in the Nebo and Cache Valley school districts as well as the International Linguistics Foundation of Sao Paulo, Brazil. He spent the 80s developing software called WordMAP.

Eventually, BYU spun off the ALP group into the for-profit enterprise Automatic Language Processing Systems Inc. (now ALPS), which conducted machine translation development through the 80s. BYU did this with many of its computer research projects.

ALPS switched its focus, with the New Directions in Machine Translation Conference Proceedings of 1988 noting that ALPS had all but ended its research goals and was focusing on purchasing and repackaging software. Ads for this software can be found in old computer magazines.

Dr. Lytle went on to help Perfect Search Corporation, a Provo company specializing in search engine optimization. Details about what they do are vague. Mysteriously, they employ one Moray King, a zero-point energy researcher.

Dr. Lytle’s final company was Linguistic Technologies, Inc. It’s unclear to me what this company does, or if it still exists. Its website hasn’t been updated since 2004. Their office is in Pioche, Nevada, a small Nevada-Utah border town that hardly seems like a place for a technology company.

Dr. Lytle died in 2010.

And that, dear reader, is where the trail ends. We’ll probably never know how much of the MTC curriculum is based on junction grammar, and how much the DoD had a say in developing the pedagogy.

Remember, though, that the CIA and FBI love recruiting former Mormon missionaries.

Sources

The Mormon Corporate Empire - Anson D. Shupe and John Heinerman

The Need Beyond Reason and Other Essays

New Directions in Machine Translation: Conference Proceedings, Budapest, 18-19 August, 1988

The Future of Translation Technology - Chan Sin-Wai

Translation Sciences Institute - https://byuorg.lib.byu.edu/index.php/Translation_Sciences_Institute

Translation—with a Little Help from Our Computers - April, 1979 Ensign

Structural Derivation in Russian - Dr. Eldon Lytle

http://www.junction-grammar.com/index.htm

Eldon Lytle’s self-written biographical information on Amazon.