Modern Mormonism has a distinctly military flavor. One of the most popular Book of Mormon stories? Captain Moroni: an ancient Mesoamerican military commander dedicated to the principles of Jacksonian democracy.

General Conferences are rife with war stories. You are told that killing is a sin unless, of course, it’s done in the service of your country’s foreign policy. Any country.

Every Mormon man I know sees war movies like Saving Private Ryan or The Patriot as exceptions to the no-R-rated-movies church doctrine. Deseret Books sells sitting representative Chris Stewart’s apocalyptic military fanfic series The Great and Terrible alongside leather-bound Book of Mormons. And so on.

As a born-in-the-covenant Mormon, I’ve always wondered if my former church is connected to the military-industrial complex. I don’t mean simply having Mormons serve in the armed forces, but the back channel connections — the greedy world of military contracting, weapons development, and technological research. It seemed obvious that in the 1980s, the Mormons, as they forged their alliance with the evangelical right, would grab a piece of the bloated, Reagan-era defense pie.

I started looking. Yes, I was searching for a conclusion I wanted to find. I’ll admit that much. But boy-oh-boy did I find what I was looking for when I stumbled upon the Eyring Research Institute, BYU’s secretive defense think tank.

What started as a passing curiosity took me down an underexplored Mormon history rabbit hole. In fact, my deep dive gave me the idea for this Substack. There’s too much for Twitter threads.

The tale of the Eyring Research Institute is complex and shadowy. This is Part 1 of the story, but I don’t know how many parts there are. Before we get into the weeds, we need to lay the groundwork.

That’s this article.

*

As expected from a patriarchal religion, family ties are critical to Mormons. Familial relationships are as good a place as any to start the story of the Eyring Research Institute — specifically, the history of its namesake.

Like other Mormons in the late 19th century, Edward Christian Eyring and his family were on the run from the U.S. government and its increasingly well-organized crackdown on polygamy. Jumping the border to Mexico, they sought refuge for their controversial sexual practices in another desert locale beyond the U.S. federal government’s reach.

The Mexico colonies took off and would prove a breeding ground for the next generation of Mormon royalty. Henry Eyring, the namesake for the ERI, was born in Colonia Juárez, Chihuahua to Eddie Eyring’s polygamist family.

The Eyring family staked their claim in the hierarchy. Edward Eyring married Emma Romney, daughter of Miles Park Romney. The Romney line produced the father-son political team of George and Mitt Romney, along with a Mormon apostle. Edward Eyring’s daughter Camilla married Spencer Woolley Kimball, the future 12th prophet of the Mormon church. Kimball, through his grandfather, was related to J. Reuben Clark as well as John Woolley, the founding father of the fundamentalist Mormon movement.

W. Cleon Skousen, the conspiratorial heart of Mormon politics, had family in the colonies. The descendants of early church leader Parley P. Pratt hid from the federal government there. Spend any time in Utah, and you’ll catch other famous names connected to the colonies, like the Turleys, Farnsworths, or Lymans.

And then you have the LeBarons, the fundamentalist Mormon dynasty that spawned their knock-off Charles Manson.

Henry Eyring found his calling studying chemistry and, at Princeton, helped pioneer approaches to apply the new science of quantum mechanics to chemistry. Here, he collaborated with Eugene Wigner, a key Manhattan Project physicist. Eyring’s star quickly rose in the chemistry community, winning him multiple awards, a chairmanship at the American Chemical Society, and shortlisted him for a Nobel Prize.

Eyring was also prominent in defense research and acted as a de facto Mormon scientific advisor, opining on the intersection of Mormon faith and science, such as it is.

As a polygamist child and bringer of good publicity for the Mormon church, Eyring secured his family’s place in the hierarchy. Eyring’s second son, Henry B., joined the Air Force at 22 and worked at Sandia Base, helping conduct nuclear weapons tests. After his stint Henry B. rose through the Mormon ranks, eventually ending up in his current position as third in command of the Mormon church. Henry B.’s son, Henry J., is now president of BYU-Idaho, despite lacking any real qualifications for the job.

**

Although Henry Eyring never worked directly for the Eyring Research Institute, the think tank bore his name in honor of his scientific achievements.

Now to the institute itself.

By the 1970s, Brigham Young University was acting more like a real college than strictly a religious education center, at least to outside appearances. Mormons were becoming less isolated and more connected to the military and business interests of the United States. Money was on the table, especially in lucrative defense contracts.

In the midst of the Cold War, any technology that contributed to nuclear missile design was a surefire way to land contracts. Thus, in 1973, Brigham Young University founded the Eyring Research Institute, a scientific think tank developing missile guidance systems, computer technologies, and electronics. Or, in other words, the tools of the Apocalypse.

When you research the US nuclear arsenal, you quickly hit brick walls. Mormon researchers also know this pain. Mormons connected to nuclear missiles? Forget about it. So you’ll have to forgive me if the corporate history is spotty. Instead, I’ll detail a few key figures in the ERI’s origin story to piece together a snapshot from these early days.

First up is Dr. Carlyle Harmon, the founder of the institute. Harmon is part of that special breed of scientists that invented something so obvious that it feels shocking it had to be invented at all. Harmon worked as the head of material research at Johnson & Johnson, experimenting with superabsorbent polymers. Together with Dow Chemical engineer Billy Gene Harper, Harmon invented the modern superabsorbent diaper, the kind you see everywhere today. He became filthy rich.

After working for decades at Johnson & Johnson, Harmon joined Brigham Young University. No doubt the Mormon leaders, dedicated as they are to high birth rates, were pleased to have hired such an illustrious name in the baby hygiene scene. When Harmon founded the ERI in 1973, he put $300,000 into the institute, almost $2 million in today’s money. His wife, Cleo, was hired on as a secretary.

The other chunk of cash ($350,000, $2.2 million today) came from the Arthur L. Swim Institute, under the guidance (maybe) of H. Dudley Swim. He was a weird guy and a challenge to find information about. During World War II, he served as a naval officer and seems to have had connections to Amos Pinchot and John T. Flynn. The latter man is best known for working with America First to oppose the US’s entry into World War II, vehemently opposing the New Deal, and spreading conspiracies about Pearl Harbor being an inside job.

After the war, Swim built a business empire in the Mountain West, even becoming the chairman of National Airlines. Swim’s strangest adventure comes to us from Jon Huntsman. Swim was Huntsman's first employer. In 1971 the two met with Richard Nixon in the Oval Office. Swim was a longtime Nixon supporter, and Nixon needed cash for his upcoming reelection effort. Nixon offered Swim the US Ambassadorship to Australia in exchange for a $100,000 campaign donation, cash only. Huntsman was tasked with collecting the money and delivering it to the President, only to have Swim die via heart attack a mere day before the illegal deal went down.

Since Dudley Swim died before the ERI was founded, it’s hard to say how involved he was in the founding, but it’s certainly an interesting story.

Swim’s son, Gaylord Swim, founded the Sutherland Institute, an arch-conservative, Christian Nationalist think tank in Utah. Yes, a vehemently anti-LGBT think tank was founded by a man named Gaylord.

With funding in place, the ERI needed a president, and found just the guy in Ronald G. Hansen. Like Dudley Swim, Hansen was a World War II vet, flying B-17 bombers over Germany during the European air war. After the war, Hansen stayed with the newly formed United States Air Force, working at what is now called the US Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine at Wright-Patterson AFB. There he primarily studied hearing protection for pilots. According to his family, Hansen was on the selection committee for the Mercury Seven — America’s first astronauts. I couldn’t find any record of this besides Hansen’s obituary, so we’ll have to take his family at their word. Hansen was the ERI’s first president and CEO, another well-connected military Mormon hired by BYU.

Brigham Young University contributed some of its own faculty to the new organization. In 1971 BYU President Dallin H. Oaks tapped chemist Leo Vernon to join the school as the BYU Research Division director. Curiously, Vernon’s page on the official BYU website doesn’t mention his involvement with the ERI, even though the website does have an entry for the institute. I had to find the name in an offhand comment from a 1991 Deseret News article where Vernon is named an ERI founder. That same article listed Armin Hill, dean of the College of Engineering and Technology and a pioneer of 3D movie technology, as one of the founders. Once again, this professor’s official BYU page doesn’t mention the ERI.

Eyring Research Institute had its team ready to dive into the murky waters of US defense contracting. It didn’t take long for the DoD and CIA to come knocking.

***

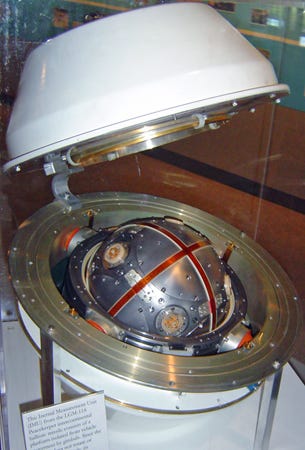

Contracts poured in. Much of the work focused on the US’s growing nuclear arsenal and its next-generation Peacekeeper missiles.

The research they did, and the products they developed, will be the focus of further installments in this series. I’ll cover all the weird backstories of the projects, and the men behind them. Some things they worked on: word processing software, virtual reality helicopter training simulations, university library software, ICBM guidance systems, and psychokinetic research. Stay tuned for more on all of this.

For this article though, let’s continue the story.

The Eyring Research Institute was founded as a tax-exempt non-profit research entity. But military contracting is a lucrative business. The authors of The Corporate Mormon Empire estimated that 70% of the ERI’s research was military contracting, at the price tag of $15 million (around $55 million in today’s money.)

That’s a lot of cash for an organization to spend. Within a few years, the ERI got its ass sued by the state of Utah. Nonprofits have to, you know, not make a profit, but the ERI was raking in the money. Under Utah law, the ERI had to prove its charitable nature.

The Utah Supreme Court brought forward its case in 1978. In the brief, they estimate that up to 80% of the ERI’s research comes from the federal government, but that these activities were not of a charitable nature. Worse still, the ERI was blatantly participating in commercial research and selling it off to municipal governments with the expectation of reimbursement. In one case, they billed the city of Provo for a feasibility study for a new ski resort.

Ronald G. Hansen was also using his position to make himself very comfortable. The Utah Supreme Court pointed out that he had given himself an extremely generous salary and had even accepted a bonus from the ERI for “a job well done.” To quote the case, Hansen’s cash flow

does not seem to be the prudent management of resources toward lessening the burdens of government and improving the quality of life of man. Such a reward seems unnecessary for an individual working for the betterment of man.

The ERI fought back, their brief using the sort of obfuscation that’s second-hand to anybody well-versed in Mormon denials. The lawyers pulled quotes from the ERI charter about the organization being a charity (as if an organization couldn’t just lie.) They pointed out that the ERI had no shareholders (fair, but money can be transferred in other ways.) The brief then goes into a lengthy discussion about the definition of “scientific”, arguing that it is impossible to disentangle the profit motive from scientific research, making every scientific endeavor the same as profit-driven research.

Finally, in classic religious-conservative sophistry, they argue that

by granting tax-exempt status to ERI and similar research institutions the Court will provide encouragement to the private sector to improve its circumstances without turning to governmental entities to do for the public what they can better do for themselves through the medium of the charitable, nonprofit research institute.

The Utah Supreme court wasn’t having it. In 1979 the ERI’s tax-exempt status was terminated. In accordance with the ERI’s bylaws, the organization was turned over directly to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

That’s right: in 1979 the official LDS church (and by legal extension, the prophet Spencer W. Kimball) owned a military think tank developing ICBM missile guidance software. Let's be clear though: BYU is owned and operated by the LDS church, with the prophet getting the ultimate say in how things are run. They already owned the ERI, now it was just official.

The Mormon church didn’t sit on its think tank for long. Within two months, they spun off the ERI into a new, for-profit entity. They didn’t get back their tax-exempt status, but now they could make as much money as they wanted, and through the faithful Mormon employees, the LDS church would skim off the top 10% of the earnings.

Business was booming. The computer revolution was in full swing, and the ERI put its shoulder to the wheel in developing commercial software. In 1981 Reagan was inaugurated, kicking off a bonanza of military spending. Along came the Strategic Defense Initiative (aka the “Star Wars program”) in 1984, a plan to develop a slew of futuristic space-based anti-ICBM weapons systems. Dr. James Fletcher, former NASA administrator and practicing Mormon, was a key consultant for the project. Wouldn’t you know it, the ERI picked up a bunch of SDI work. Weird.

****

The trail starts to run cold here. In 1988 Carlyle Harmon was kicked out. According to his wife, Harmon said: "I was squeezed out of my own Institute. I truly felt like a man without a country." By this time, the ERI had been spinning off company after company, cannibalizing itself into a network of private, Mormon-run entities mainly focused on computer technology. At some point, the Independent Order of Foresters (an insurance benefit society) and Alenia (the umbrella company for a network of Italian defense contractors) bought the ERI. In 1991 there was an effort to get it back under Utahn control.

That’s where we’ll leave the history for now. As mentioned above, I’m going to dive into all the research in further installments.

In a real way, the ERI is the precursor of the Silicon Slopes Utah economy. Lehi’s tech industry was built in no small part from the influx of jobs at the National Security Administration’s Utah Data Center, much like the ERI’s research was built on the needs of American nuclear strategy. Like the current Utah economy, the ERI funneled money to the top of its organization and proceeded to give those lucky employees the foundation to start their own lucrative enterprises. Connections within Mormon circles, were, and still are, the way the Utah tech economy runs.

What does it say about members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints that, despite their claims of Christlike love, they were willing to dive head first into the most odious technologies of the US military — the nuclear missiles? This was an organization run by BYU, under the auspices of Dallin H. Oaks, second in command of the current Mormon church. And there was no moral guidance, no concern that they were building the tools that could end the human race.

Maybe they were so focused on the allegedly imminent Second Coming of Jesus Christ that they couldn’t see the immorality of their actions. Maybe they just didn’t care, and, like good Mormons, never learned to say “no.” Or maybe they saw their role as hastening the return of the Savior, leaving the rest of us heathens to burn in the ERI’s nuclear fireballs while the blessed faithful ascended with Even Jesus Christ to that great Celestial Room in the sky. Make sure your temple robes are on your right shoulder and don’t forget your handshakes, folks.

SOURCES

Court Cases

https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1263&context=uofu_sc2

https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1749&context=uofu_sc2

Swim

https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/LH8V-4DF/hubert-dudley-swim-1905-1972

Right Turn - John E. Moser

Barefoot to Billionaire - Jon Huntsman

https://www.nixonlibrary.gov/taxonomy/term/3489

http://www.nalalumni.org/history-of-nal.html

Other Things

The Corporate Mormon Empire - Anson D. Shupe, John Heinerman

https://archive.org/details/sciencetechnolog465tell/page/76/mode/2up?view=theater&q=eyring

https://www.premierfuneral.com/obituaries/Ronald-Hansen-23208/#!/Obituary

http://archives.lib.byu.edu/agents/people/8342

http://www.mormonstoday.com/011130/P2CHarmon01.shtml

https://cen.acs.org/articles/86/i23/Remembering-Henry-Eyring.html

https://www.deseret.com/1991/9/18/18941778/new-ceo-of-eyring-research-aims-to-triple-its-revenues-within-5-years

https://archives.lib.byu.edu/agents/corporate_entities/3165

I worked with Bruce C. Wydner, C.E.O., The Inns of the Temple, inc. a 501 c 3, from 2006 until his death. and I have digital copies of all his contracts and related documents made with ERI, his hired programmer Bruce Bastian (WordPerfect), and his brother's company Wiedner Communications. Send me your email and I send them to you. dbp653@yahoo.com. And what about that E.R.I. spinoff Superset Group that was be Novell's developers? Why did Ray Noorda try to save WordPerfect from acquisition? Deep!

I have some information about Swim and the ERI. Can you email me at dorrieharbottle@gmail.com?