(Note: I sent this out with a typo in the title, real professional writer here.)

Mormons are outdoorsy people (or at least like to think they are), embracing a culture of camping and hiking, especially when planning activities to keep Mormon teenagers occupied throughout the year. If you’re in Utah or Idaho, this means exploring some of the prettiest mountain landscapes on Earth. Mormons in Las Vegas have no such luck.

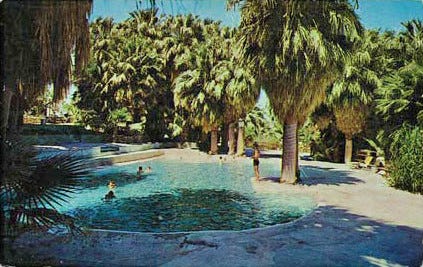

Outdoor activities for Las Vegas youth often mean hiking blasted desert landscapes in the scorching summer heat, desperately fending off heat stroke, and avoiding rattlesnake holes. There are only two exceptions to this bleak state of affairs: Mount Charleston, a cool mountain northwest of Las Vegas, and Warm Springs, an oasis of greenery in Moapa Valley across the interstate from the Valley of Fire. Greenery, shade, water! What luxury.

Driving to Warm Springs is a bit of a magical experience. You’re traveling up the I-15, watching endless desert landscapes stream by, and then suddenly, you pull off the highway, drive a few minutes, and you’re transported from harsh barrenness to an almost tropical oasis. It sure beat hiking along the Colorado River, where youth activities felt more like penance for sins.

Warm Springs is owned by the Mormon church and operated as a park for stake activities, youth conferences, ward activities, etc. Like many Mormon properties near Las Vegas, Warm Springs ties back to Howard Hughes. This is the story of how it changed from a showgirl resort to a Mormon activity park.

*

Howard Hughes’s most famous Las Vegas period was the years he spent cooped up in a Desert Inn penthouse, slowly wasting away as his Mormon advisors kept him doped up on painkillers and cut off from the outside world. But his interest in Nevada real estate started earlier.

Hughes’s first taste of Nevada came in 1931 while having an affair with silent film star Billie Dove. Dove wanted a divorce from her husband, so Hughes brought her out to Nevada, aiming to live in Las Vegas for six weeks, establish residency, and obtain the divorce. Together the adulterous couple shacked up on a farm outside of Las Vegas. They literally lived in a shack — a concrete structure on the property not much bigger than an average kitchen. Unfortunately, living in a concrete shed didn’t qualify as a “residency,” so the plan was foiled. Still, Hughes got his first taste of the Nevada desert and liked it.

Hughes made his first Nevada real estate move in 1953 with the purchase of 25,365 acres near Las Vegas. Grouped under the name Husite, it wasn’t exactly clear what Hughes wanted to do with the land. Las Vegas reporters speculated that the land would eventually become a sprawling military-industrial complex for guided missile development, but it wasn’t until the 80s that Husite was finally developed as the Summerlin master planned community.

While Husite was shrouded in mystery, Hughes was clear about his plans for another parcel he bought outside of Las Vegas. This he intended to make into an airport to compete with McCarren Field, now Harry Reid International Airport. Instead of handling conventional commercial airlines, Hughes wanted to turn his land into the first purpose-built airport for supersonic airliners. In the 60s, these seemed like the future of aviation, promising lightning-fast travel across the globe. This futuristic vision never took off, with only two supersonic airliners ever working, and the Hughes plans fell into obscurity.

This wasn’t Hughes’s only misguided Nevada purchase. Hughes, allegedly, wanted to purchase mines throughout Nevada to preempt rising gold and silver prices. At this point, he was under the control of Bill Gay and the Mormon Mafia, so it’s not clear whether this was Gay’s idea or Hughes’s. Either way, Gay hired John Meier of Watergate fame to scout around Nevada, buying cheap mines and hoping they could still produce valuable metals. Nevada locals were stumped but pocketed the cash. Unsurprisingly, the mining plan never panned out.

Hughes’s ranch purchases were more successful. He bought Vera Krupp’s ranch in Red Rock Canyon, outside of Las Vegas. Nestled among the striated peaks, the ranch was used by Hughes employees for R&R before being sold off to investors. Now it’s a state park. The other big purchase was Warm Springs Ranch.

**

Warm Springs is located near Moapa, Nevada, a little town settled by Mormons on the Muddy River, directly across the I-15 from the Valley of Fire. Area 51 is to the northwest; St. George, Utah to the northeast. At some point in the 20th century, it was leased by Jim Haworth, a Mormon rancher. For 35 years, he managed the ranch as it shifted hands from Francis Taylor to Howard Hughes and eventually the Mormon church.

Howard Hughes allegedly first discovered the ranch during his many flights over the Nevada landscape, while he was still able to fly. I’ve found two stories about why he wanted the property. The first, as recounted in Geoff Schumacher’s Howard Hughes: Power, Paranoia, and Palace Intrigue, is that Hughes purchased the land to entice his estranged wife Jean Peters to live with him in desert seclusion. However, the Warm Springs official website says that Hughes bought the land as a resort for his favorite Vegas showgirls. Either way: sex.

The land has two parts. One is a large cattle ranching operation, the reason Jim Haworth leased the land in the first place. The other is a large recreational area situated around the titular Warm Springs. The springs are the headwaters for the Muddy River, making the ranch an oasis. The largest spring, Big Muddy, is a natural pool of crystal clear water.

The unlikely water supply makes Warm Springs an environmental island in the Nevada desert. Twenty-eight endangered species live in this shady oasis, including the Southwestern willow flycatcher, yellow-billed cuckoo, and the desert tortoise. Six species are found only at Warm Springs and its environs, including the endangered Moapa dace fish. An iconic feature of the land is its massive California fan palms, which aren’t native to the area. Fortunately, the trees provide a habitat for the native species but also fuel for fires during dry seasons, which are basically every season nowadays.

By 1971 the Mormon Mafia was running the Hughes empire, putting Bill Gay and his friends in charge of managing the Warm Springs ranch. It went badly almost immediately. Jim Haworth now had to report to white-collar executives with no ranching experience. Haworth and Gay were just from different cultures within the Mormon sphere. Bill Gay exemplified the suburban, business-oriented strain of Mormonism, while Haworth had that pioneer vibe, traveling around the country and raising livestock. He was the sort of hardscrabble Mormon that Wasatch Front residents think they are while driving their massive SUVs to pick up Sodalicious before heading back home to a vast suburban tract. Gay, on the other hand, was the new breed of Mormon, enjoying the benefits of his pioneer heritage without having to put in any of the work. He was a business executive, earning his fame in the Mormon sphere through corporate prestige. You can imagine the two men meeting and immediately hating each other — two different cultures, united under the roof of Mormon faith.

Gay and company simply didn’t know what to do with cattle. According to Jim Haworth in Howard Hughes, His Other Empire, and His Man (and recounted in Geoff Schumacher’s book):

Being part of a multimillion-dollar outfit, Jim thought he could relieve the strains on the ranch, but soon found that those in command had no intention of helping Mr. Hughes make the ranch a pleasure and success… Through mismanagement of the property division, Hughes could not help but lose the majority of the Krupp cattle the first year. They did not die. These good breeding animals were taken to slaughter by Gay’s men, probably for Hughes’ hotel beef. Meanwhile, several hundred thousand dollars were wasted on the Krupp ranch, fixing it up as a playhouse for Hughes’ high executives from Las Vegas and Los Angeles… [they sold] off the valuable Brahma cattle that Frank Taylor and [I] had developed. They didn’t know a damn thing about ranching.

When Hughes died in 1975, his empire fell apart. Internal battles between the Mormon Mafia and other Hughes executives spawned dozens of lawsuits. The financials were a mess, leading to the empire being sold off piecemeal. In 1978 Warm Springs went up for sale for $8 million and was bought by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. The church sold off parts of the cattle ranching operation and focused on running Warm Springs as an activity park, which is what it still is today. In 2007 more of the land was turned over to the Nevada government for conservation efforts.

Disaster struck in 2010. Those California fan palms are pretty but are a fire hazard if not properly maintained. Overgrown fronds dry out in the sun, providing quick-burning fuel. The Mormon church, following the tradition of Bill Gay, had not adequately maintained the site, leaving day-to-day management to unpaid volunteers. A fire broke out and quickly swept through the area, fed by the overgrown fronds. The 75-acre site was completely devastated, with foliage burned away and the buildings destroyed. Fortunately, nobody was onsite besides two elderly Mormon missionaries who escaped without harm.

The damage was so bad that it took seven years to repair, after which the church gave the management duties to the Tule Springs Stake in suburban Las Vegas, currently run by a prominent orthodontist. Jim Haworth spins in his grave.

***

Warm Springs wasn’t the first or last time the Mormon church invested in ranching.

In 1947 Mormon apostle Henry Moyle pushed the church to start buying up large swathes of agricultural land in Florida. Under the name Deseret Ranches, the church now owns 600,000 acres of land near Orlando, cultivating 44,000 heads of cattle. The ranches are officially owned by the church, but obscured by a variety of umbrella companies so that the church can run it as a for-profit enterprise. Deseret Ranches is one of the few examples of the church acknowledging that it runs for-profit businesses. Gordon B. Hinckley, future prophet of the church, described them in the April 1991 General Conference:

Then we have some commercial farm properties. I spoke earlier of the reserves of the Church. Prudent management requires that this money be put to use. In that process, we have purchased and hold some good, productive farms. They are well operated under capable management, and they yield a conservative rate of return. We have felt that good farms, over a long period, represent a safe investment where the assets of the Church may be preserved and enhanced, while at the same time they are available as an agricultural resource to feed people should there come a time of need.

Up until recently, the church called “missionaries” to work on the ranch in various auxiliary positions. Missionaries are not paid.

Deseret Ranches is connected to AgReserves, another for-profit entity under the official church holding company. AgReserves is a diversified, multinational corporation that not only runs the church’s agricultural holdings but also coordinates real estate investments in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Canada, and the United Kingdom. They don’t just own the church’s farms, they also have a diverse real estate profile including office buildings, malls, and resorts, making it one of the most valuable real estate portfolios in the world.

Beef takes up a lot of water, and with climate change worsening our environment water supplies will become more and more scarce. The Mormon church recognizes this, moving to secure water rights and diversify away from cattle.

Warm Springs fits into this new investment strategy, giving the church groundwater rights in the area. In 2006, the church scored a $7.2 million deal with the Southern Nevada Water Authority to lease Muddy River water until at least 2026. Las Vegas is under threat of losing its water supply, with drought conditions worsening every year. What few water sources remain will become increasingly valuable, and the Mormon church is sitting on top of one.

They’ve also been making future plans in Florida. The church knows that massive cattle operations will be impossible in the future, and is already making plans to turn Deseret Ranch land into a residential area by 2080. In six decades, the church will have built a new city in Florida, presumably owned and operated by Mormon entities. As part of this plan they’ve proposed building a second reservoir on the land, leading Florida residents to speculate that the church is moving to control and profiteer off water rights in the area. From CBS:

Veaudry isn't buying the compromises, especially the proposal of a second reservoir.

"Why do they need another reservoir?" she said. "They're trying to get future water rights."

Deseret already is in six-year a legal battle with state regulators over whether it can charge public utilities in central Florida to use the water from a reservoir on its property.

"Deseret has had a vision for a long time of being a producer of potable water to sell to others," Lee said.

Hardly any of today's planners likely will be around when the land is built out by 2080. Because of that, observers say it will be an ambitious task to make sure that what is proposed in 2015 is carried out by 2080.

Finally, you have 12,000 acres of land in Eastern Washington that both AgriNorthwest, another church-run entity, and Bill Gates wanted to purchase. AgriNorthwest won the bidding war, scooping up all this land for the Mormon church. Right now it’s used for cattle operations, but the water on the land is where the future money is. From the Daily Beast:

The 12,000 acre assemblage in Eastern Washington currently generates revenue through large-scale farming (potatoes and onions) and cattle herding, but with an increasingly warmer climate, it’s the water rights that come with the property that may end up being its most valuable asset.

Dan Haller, a Water Resources Engineer with Aspect Consulting, a water rights consulting firm operating in the Northwest, knows full well about the value of “favorable water rights”, especially in the Columbia River Basin. According to Haller, water here is “fully appropriated”—meaning that if you want it, you can’t just apply to the Washington State Department of Ecology for a new water right; you have to buy and transfer existing rights. “Water rights operate under the same supply and demand principle that other scarce resources do; as the need for additional food production grows, it creates upward pressure on the price of water rights,” Haller says.

From Howard Hughes to a Mormon activity park, Warm Springs is another cog in whatever future plans the church has.