Total Integration: BYU and America's Nuclear Strategy (ERI Pt. 8)

Part 8 of my ongoing series covering BYU’s Eyring Research Institute, their secretive weapon and computer research lab. Click the index at the top of the site for previous installments.

It did not take long for the aviation pioneers of the early 20th century to realize that sending relatively untrained pilots into the skies would lead to scores of mangled and dead aviators. However, technology at the time limited the ability for aircraft instructors to simulate the experience of flying while safely on the ground. In the early days, a few hours of basic airplane operations was all a pilot got; they needed to learn the techniques of flying on the job and in the sky.

World War II saw improvements, with the United States investing in hydraulically powered aircraft simulators, placing pilots in replica cockpits that would pitch and turn like a real airplane. The advent of computers led to another major breakthrough. With lightning fast processors, complicated electronic systems, and high-fidelity screens, instructors could simulate flight conditions virtually identical to the real thing. These early simulators reached their apex in the Apollo program. NASA built spacecraft simulators so realistic that the astronauts would spend hours and hours on end simulating every conceivable failure they could face on a lunar mission.

As computers became more powerful, programmers could begin simulating larger systems, conducting experiments on whole virtual worlds. This power found application in the most lucrative field of the Cold War: planning for nuclear conflict. Unlike pilots who even with minimal training could muddle through their first flight, a nuclear conflict is a one-and-done thing. You can’t create a miniature one to see how things play out, but military planners needed ways to test their ideas. Because once the missiles launched there was no way to refine the strategies on the fly. Every precise detail needed to be decided on beforehand. High-tech computers provided the solution. With the right programming military planners could test countless hypothetical scenarios, honing on their preferred strategy for annihilation.

BYU’s Eyring Research Institute, being a cutting-edge computer research firm, was on the forefront of computer simulations. Through their connections they built a full-fledged testing program to test Minuteman nuclear missile strategy inside a confined virtual world.

*

Strange lights glare in the night, making the mountains shine, and a grumbling roar rolls across the desert. By day enormous clouds of steam-white smoke billow up . . . and drift over hills and valleys. Monstrous vehicles with curious burdens lumber along the roads. All these strange goings-on mark the development of the Minuteman, the solid-fuel missile that its proponents confidently expect will ultimately replace the liquid-fuel Atlas as the U.S.'s standard ICBM.

Times Magazine

Aerospace technology advanced at breakneck speed during the start of the Cold War. Jet fighters were introduced into the services to be replaced by newer models within a few short years. Bombers were constructed only to find themselves rendered immediately obsolete in the face of new Soviet defensive tech. Nowhere was this head spinning progress more apparent than in rocketry. In less than two decades, the Americans had gone from experimenting with captured Nazi V-2s to fielding an always-ready nuclear missile force of world-ending proportions.

The early nukes in the US arsenal were all fueled by liquid rocket propellants stored in tanks. While powerful, these fuels would gradually seep out of the tanks, requiring crews to fuel up the propellants before launching their missile; a troubling delay when a war could be won or lost in minutes. A better option was solid fuels. Rocket fuel of this type has the consistency of wet cement and is poured into the rocket body during construction. Solid-fueled rockets could sit within a silo for years without jeopardizing their flight status and, as an added bonus, could be easily mass-produced.

Starting in the late 50s, the government spent a great deal of time and money researching solid-fueled ICBMs. Out of their research came the Minuteman, a missile so named because it would be ready to fire with short notice. To test the rocket, the scientists needed a place where they could light off engines and handle noxious chemicals without worrying about nearby inhabitants. The vast desert tracts of Utah were just the ticket.

As if it grew out of the ground itself, a nuclear missile production enterprise rapidly emerged in Utah. What were once empty desert landscapes — important to nobody the government paid attention to — turned overnight into a gigantic testing ground. Along with the equipment came tens of thousands of workers, immediately changing the economy of northern Utah.

Away from the test grounds stood Hill Air Force Base. In yet another exercise in military gigantism, Hill is a massive, sprawling complex covering 7,000 acres of the Wasatch Front. The base’s size was driven by its purpose. Starting in World War II, the military used the base to store its surplus airplanes. Gradually, the storage facilities were joined by maintenance depots and manufacturing plants. At some point in the lifespan of any US air weapon it has probably found its way through Hill. In the case of the Minutemen, they were manufactured in the Boeing facility on-premises.

The missile industry wormed its way into the fabric of Utah life. From the northern test ranges down to Provo, everybody knew someone who was working for the military in some capacity. When it came to cutting-edge research BYU’s Eyring Research Institute was willing to contribute their expertise.

The question of the ERI’s involvement in the Minuteman program has come up before. The eccentric computer engineer Bruce Weidner was convinced that his code for word processing software was modified and reused for the missile’s guidance system. He also alleged that it was repackaged as WordPerfect. But, as covered in the linked article, it is hard to find much details about the ERI’s involvement in the program. For one, the ERI remained tight-lipped throughout its life. The newest Minuteman models are also still an active US nuclear missile, making information on their technical details hard to come by.

Some people messed up though. In a Facebook group for ERI alum (which now seems to be cached, but the main page is still available) the administrator mentions TISC, the Totally Integrated Simulation Computer. They say that the TISC was used to simulate the launch and flight of the Minuteman II and III missiles. Interestingly, they claim that this was the first funded project that the ERI earned.

Other than that, the TISC has not left much of an information trail. A Daily Herald article from 1981 mentions TISC, as does a declassified research paper entitled A Study of Embedded Computer Systems Support Volume VII, Requirements Baseline: Operational Flight Program. The paper gives some details of TISC’s operation, although the it calls the system the Total Integrated System Capability.

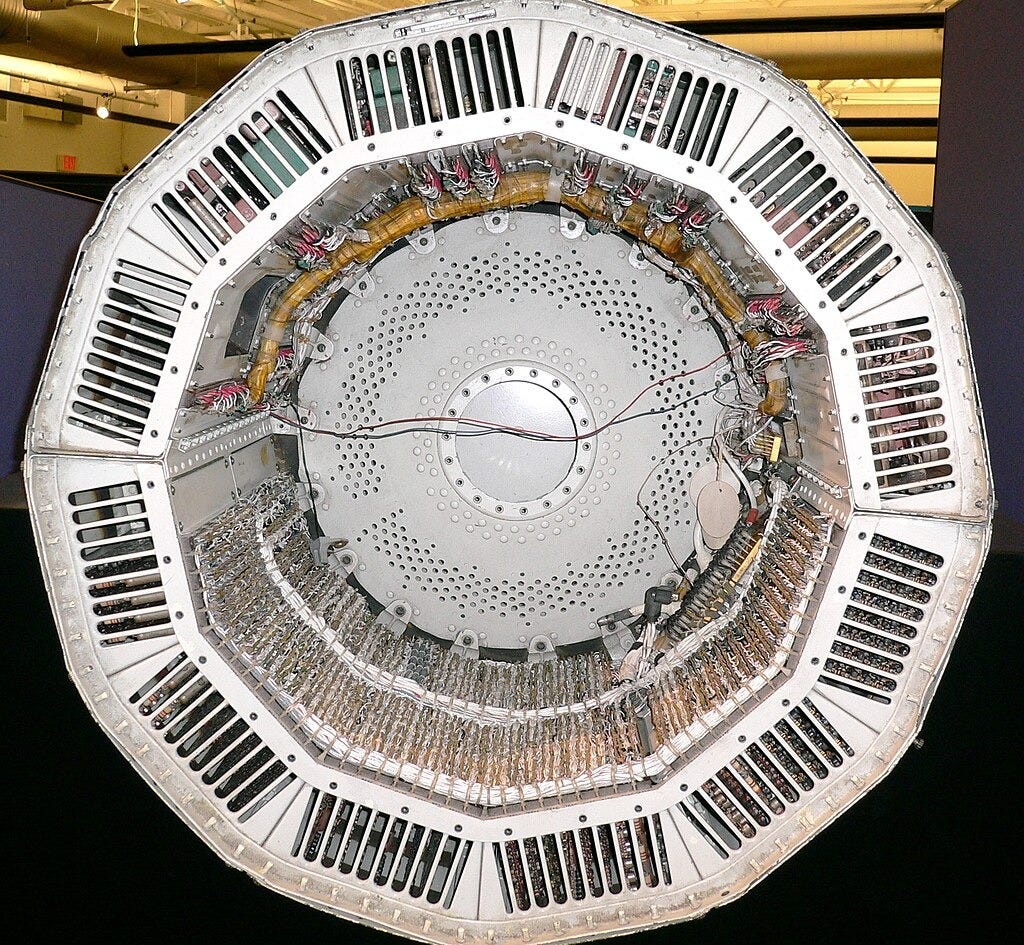

TISC consisted of a D37C, the Minuteman’s computer “brain”, hooked up to two NOVA commercial computers. In operation TISC would simulate all aspects of the missile’s flight, from ground prep to terminal impact. In effect, the NOVAs were tricking the D37C into acting like it was flying a mission. They could run tests over and over again, slowly refining the actions the missile would take if it was launched for real. All TISC installments were at Hill Air Force Base.

ERI employees also have evidently been tight-lipped about their involvement with the program. One Lee Swindlehurst worked on the program, but it is not mentioned on his Wikipedia page or his University of California, Irvine faculty page. The only mention available is on this random career summary.

One person proud of his work, however, was the project lead: John P. Pratt.

Pratt was born a Latter-day Saint and from a young age felt that he was in touch with the divine. On his webpage (which has a wonderful early internet charm and is thus only sort-of navigable) he recounts early religious experiences; childhood prayers being answered, sacred baptismal experiences, and a vision of his future family. From the start, Pratt felt like he had one foot in the next world.

His career started in earnest in 1972 when took an interest in politics. Under the recommendation of Ezra Taft Benson — future President of the LDS church but then apostle — he read Gary Allen’s None Dare Call It Conspiracy. The book posits that all of the government is under control of a few elite individuals called The Insiders. These Insiders are working to implement a new world order organized along the lines of the Communist Manifesto. Benson, affiliated as he was with the Bircher movement, recommended it and echoed the conspiratorial contents of the book in his sermons to the church. Pratt claims that the book changed his life, opening him up to the truth about the dark forces working with the government to subvert our freedom.

To fight these nefarious forces Pratt ran down to the local Republican office and signed up to be a Precinct Committeeman during the ‘72 election. Unbeknownst to him (somehow), the Republicans expected him to campaign for Nixon. Pratt had already decided that Nixon had been chosen to be the president by the Rockefellers in a secret meeting in Chicago and had planned to vote for John Schmitz and the far-right American Independent Party. Realizing that by campaigning for Nixon he would become a tool of the Elite, Pratt promptly quit.

Pratt was hired by the Eyring Research Institute in 1976 after completing an undergrad in both physics and math as well as a PhD in Astronomy. The ERI was already four years old at this point, having been founded the same year that Pratt became politically radicalized. They now had the new TISC project to work on and assigned Pratt to lead the team of nine software developers for the simulation computer. This was his first scientific job. One might suspect that helping the United States military develop nuclear missiles would be considered one of the most overt ways of helping “The Insiders,” but apparently Pratt did not find any contradiction between his job and political beliefs. Anyways, the missiles would be fired at the Communists, would they not?

Like with the above sources, Pratt does not share the details of TISC, but his website shows that he became increasingly interested in mystical powers during his time simulating nuclear war. On February 28th, 1980 the ERI held a seminar for their managers to teach them how to have meaningful dreams and even use them to change the course of future events. They claimed that dreams came from the right hemisphere of the brain, but that the managers of the ERI were mostly left-brained computer programmers. By learning how to use the right hemisphere, the managers could unlock their visionary potential.

Pratt took the advice to heart and began practicing. Within two weeks he had his first meaningful dream. Pratt was always a morning person, and on March 12th had a dream that he would talk to his boss at Hill Air Force Base and be given a schedule change that would allow him to start working at 7 a.m. The next morning these events happened, just as he dreamed them.

Now armed with the power to either receive visions in his sleep or use his dreams to influence the future, Pratt looked for more ways to exploit this gift. While he found his work simulating nuclear missile attack strategies interesting, Pratt began to realize that his true passion lay in astronomy. In 1981, he had a dream where he was driving along a road to an observatory where he had been hired as an astronomer. The road, however, was blocked and under construction. A spectral man stood in front of the block and told Pratt that the road was not yet constructed. Pratt took this as a vision confirming his future job as an astronomer.

The ERI’s contract for the TISC system ended in 1988 and the Air Force decided not to retain their services. Suddenly without a job, Pratt turned to Alan Ashton, the founder of WordPerfect. For years, Ashton had tried to recruit the nuclear missile programmer to join the company, but Pratt had preferred to not work in business. Now he was willing to take the offer. On Pratt’s first day he drove to the office in Orem, only to find the road blocked. The image was identical to his dream. At the end of the road was not an observatory, but the WordPerfect office. However, with a new stable job Pratt could spend his free time exploring his interest in astronomy, conducting freelance research of the astronomical calendars of ancient civilizations.

This was his passion for the rest of his life. He held stable jobs with various tech companies but seems to have spent all his free time writing. His website contains dozens of articles and pages detailing his theories about ancient calendars, and even inventing some of his own. It is quite the rabbit hole and absurdly detailed, more than any one person can or should take in.

Eventually he stopped restricting himself to historical calendars and began inventing his own or updating ancient calendars to make them more accurate. Often, these calendars had complicated esoteric meanings. Take, for instance, his Jubilee Calendar. Based on another calendar system he derived from the Book of Enoch, the Jubilee Calendar seeks to account for the idea that God divides time into both 12 and 7 parts. Conveniently, the Jubilee Calendar places the resurrection of Christ and the Ascension of Moses on the same date. Neat!

Another interesting calendar is the Perpetual Hebrew Calendar. According to Pratt, God himself uses a perfect version of the Hebrew calendar, the one in antiquity becoming less accurate as time goes on. The PHC is Pratt’s attempt to recreate God’s calendar using complicated mathematical and archeological reasoning. More accurately, Pratt worked backwards and fenangled his calendar to create synchronicities between religious events. For example, the PHC places the date that Joseph Smith claimed to be visited by the angel Moroni and told of the Golden Plates as 15 Tishri, the Feast of the Tabernacle.

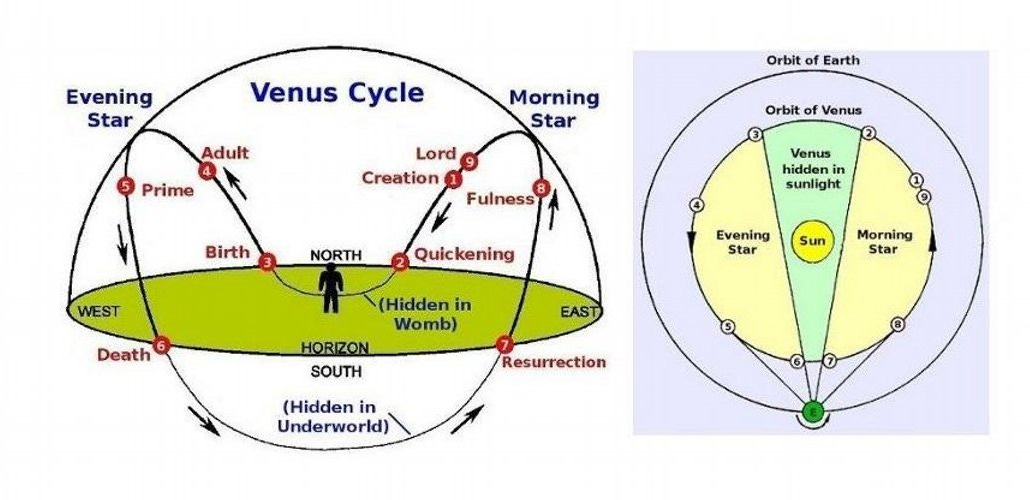

These temporal explorations would ring familiar to any reader of the Meridian magazine, for Pratt wrote extensively for them. The Meridian magazine is an unaffiliated Mormon magazine; a sort of catch-all magazine with contributors from throughout the Mormon spectrum. Pratt’s contributed articles like “Uranus Testifies of Christ,” an unfortunately named description of the faith building characteristics of the Uranian orbit, or “Venus and the Beginning of Mortality,” an exploration into how the apparent path of Venus echoes Mormon apotheosis.

This is all on the fringes of mainline Mormon belief. Eventually Pratt dropped right off, severing his ties with the mainline LDS church and following Mauricio Berger. This Mormon schismatic claims to have translated the Sealed Portion of the Book of Mormon, the part of the Golden Plates that Joseph Smith was not allowed to translate back in the 1820s. Mormon theology states that at some point before Jesus returns the Sealed Portion will be translated. It’s a sort of perpetual sequel bait. Berger says he did it and Pratt followed along. Click on Berger’s website and you’ll see Pratt on the splash page performing a baptism. He’s the old guy with the headband. Naturally, the mainline LDS church is very opposed to prophetic claims like Berger’s but Pratt seems to have remained affiliated with Berger’s group until he died in 2021.

Pratt’s story is only one of many from the nuclear landscape of the Wasatch Front. While the Mormon church fought against the placement of nuclear missiles in Utah during the 80s, concerned that silos would make them a target for the Soviets, the powers of the state don’t seem to have a problem building, supplying, and simulating these tools of mass destruction. TISC gave the military the tools to iterate through nuclear strategies, finding the most effective ways to annihilate people on the other side of the world. For an institution that prides itself on arrow-straight moral guidance, it’s shocking that wholesale murder does not rise to the level of the condemnable.

These aren’t concerns limited to the past. Hill Air Force Base still maintains and develops the systems for the missiles. Drive north until you get to Clearfield and around Exit 335 look to the right. Towering over the BAE Systems-branded Jimmy John’s, you’ll see the nosecones of two Minuteman missiles, reminding you of a past that lives on, for the Minuteman is getting old, and its replacement is under development. It’s been in the nuclear arsenal since JFKs presidency, and if it goes away so does a part of the Utah economy. The successor, the LGM-35 Sentinel, has been beset with cost overruns, ethical concerns, and technical issues. Facing increasing scrutiny within the Senate, a group calling themselves the ICBM Coalition has organized to champion the needs of the Sentinel. It’s a small group, mostly from deep red states, and one of them is Utah Senator Mike Lee.