Ushering in Jesus's Second Coming with Word Processing Software - ERI Pt. 2

Check out Part 1 of this series for the general history of the Eyring Research Institute. Some of the key names reappear here, so I’d highly encourage you to read Part 1 if you haven’t.

A secretive society’s ability to maintain its mysteries is necessarily limited by the communication technology of the day. In the Mormon case, secrecy practices designed for an era of telegraphs, letters, and word of mouth worked in the 19th century but by the 20th, the cracks were starting to show. In the 21st century, widespread internet access has blown the lid off the Mormon operation, exposing unsavory religious practices and historical episodes to the harsh glare of social media discourse.

They know the internet is a problem. Modern church leaders constantly warn their flock about the “dangers” of online information and periodically order their followers to refrain from using social media for a week or so.

They weren’t always this paranoid. In the late 60s - early 70s, as internet technology staggered out of its infancy, Mormon leaders saw the burgeoning electronic revolution as the fulfillment of prophecy and lauded the new communication technologies as the key to spreading their gospel throughout the world.

In an example of modern Manichean duality, the Mormons sowed the seeds of their destruction within the shadowy Eyring Research Institute. In this installment of my ERI deep dive, we’ll look at how the institute laid the foundations for modern word processing software. However, what started as a straightforward software development project turned into an enigma when David O. McKay and Cleon Skousen hired a latter-day mad scientist — Bruce Weidner. His work is sitting on your computer right now — it’s (allegedly) the foundation of WordPerfect and Microsoft Word. Like any good creation myth, the story of how the ERI invented word processing depends on who you ask, creating one of the strangest enigmas in Mormon history, one that changed the world of computer software and (allegedly) nuclear missile guidance.

*

Acts 2: 6-8 reads: “Now when this was noised abroad, the multitude came together, and were confounded, because that every man heard them speak in his own language.”

Thus were the events of the first Pentecost. The apostles had gathered in a Jerusalem house. After the dreadful day of Christ’s crucifixion, they had all witnessed his glorious resurrection. The newly risen Master proclaimed words of prophecy before being taken up into a cloud, helped by two men in white apparel. Before they vanished, these two mysterious strangers prophesied that Jesus would return.

As the apostles sat together in this Jerusalem house, probably discussing the events they had witnessed, jets of flame entered the building, settling on each of the twelve men. Suddenly, filled with the Spirit of God, engulfed in fire, they began speaking in foreign languages. A crowd gathered, witnessing this miraculous event.

In Mormon premillennialist theology, this verse takes on a prophetic meaning. Like the ancient Christians, the Mormons will preach their true gospel to the world in every man’s own language. Only then can Jesus return. In the 20th century, this prophecy's fulfillment hinged on translating the Book of Mormon — the church teaches that by simply reading the book, you’ll get converted to Mormonism. So, before Jesus comes back, the Book of Mormon needs to be available in all languages.

Mormon prophet David O. McKay proclaimed in 1966: “I appreciate and realize the accomplishments, to a certain degree, of this wonderful atomic age in which we are living. Scientific discoveries of today stagger the imagination… The discoveries and inventions of this age are unequaled by any previous period in the world's history, discoveries latent with such potent power, either for the blessing or the destruction of human beings.”

This was taken as a prophecy, opening up the door for the church to incorporate the tools of modernity into its desire to preach a Jackson-era theology. You can’t convert people with a nuke (despite what Curtis LeMay might have believed), but the nascent field of computer science promised instantaneous translation and worldwide communication. Mormon leaders like Spencer W. Kimball and Gordon B. Hinckley picked up McKay’s thread, effusively praising computer science as a tool to usher in the Second Coming. Like, check out how prominently communication technologies feature in this collage-like painting of Gordon Hinckley.

When BYU set up the Eyring Research Institute in the early 70s, computer science was a top priority. Specifically, they spent those early years attempting to perfect machine translation software. Translating the Book of Mormon by hand might make for a good story, but it doesn’t scale to a worldwide church. Computers were the ticket.

In this milieu of digital enthusiasm, two young Mormon programmers — Bruce and Stephen Weidner — began work on rapid, computerized Book of Mormon translation.

Bruce Weidner dove into the code, ready to build a machine that would bring Jesus back and usher in the Millennium — the utopian 1,000 years that Christ would reign on the Earth in a perfect Mormon paradise.

But before we continue the tale, a word on sources.

The story of Bruce Weidner and WordPerfect is a tangled web of he-said-she-said contradictions. I’ve identified three narrative threads that, like the Synoptic gospels, line up on some points but are completely contradictory on others. They break down something like this:

The official version: The recollections of the WordPerfect and Novell founders, BYU affiliates, Deseret News, and early 2000s court cases.

Bruce Weidner’s version: His own recollections, his legal disputes, and stories from obscure ERI members that didn’t end up with a lucrative tech company.

The Messianic version in The Fifth and Sixth Thousand Years: Mostly a bizarre internet forum I found where a user posted messages from Bruce about the Second Coming and other religious matters. This user also wrote an unauthorized sequel to Cleon Skousen’s The Five Thousand Year Leap which includes Bruce Weidner’s story, but puts a more messianic spin on the tale. I believe the details are correct in broad strokes.

Now back to our story.

**

After McKay’s prophecy in 1966, attention turned to BYU and its nascent computer science program. If anybody could build a system to spread the gospel to the world through telecommunications, it would be the Mormon church’s scientists. According to Source 3 and some vague references from other ERI employees, Cleon Skousen and McKay instigated a church-run machine translation effort.

Skousen was the beating heart of Mormon politics in the 70s, synthesizing Mormon political theology with right-wing conspiracy thinking. Having the ear of Mormon leadership, Skousen’s ideology shaped, and continues to shape, the church’s political theories, all without ever having become a General Authority.

Weidner’s early biography is murky. According to his brother Roger, Weidner worked as a linguist for the CIA and Pentagon. In this capacity, he learned up to 12 European languages and developed a methodology for rapidly learning foreign tongues. He wrote a textbook called “The Quickest Way To Learn Spanish Is To See IT!" which brought him to the attention of McKay, Skousen, and Gordon B. Hinckley.

(Side Note: Bruce spelt his last name as both “Weidner” and “Wynder” throughout his life. Supposedly he thought that the later spelling was easier to pronounce than the former.)

In a 1973 meeting, Skousen laid down the general direction of the ERI’s translation efforts, told Weidner he would fulfill McKay’s prophecy, and described a vision for the translation software. Using these tools, the Lord would teach the Saints true doctrine. God would use Weidner’s work to usher in the Second Coming, bringing about the perfection of the Earth and Jesus Christ’s reign on the planet. Oh, and all those dirty liberals, radicals, communists, feminists, and civil rights activists would get burned in apocalyptic fires.

These details come from Source 3, so a grain of salt is necessary. Weirdly though, this source mentions that McKay prophesied that the church would create a “Worldwide Interlingual Telecommunications Utility.” In 2012 somebody named Allen Martin incorporated a company with this exact name based out of Eagle Mountain, Utah.

Weidner started coding on a PDP-11, hoping to make his software compatible with the full range of IBM machines. The ERI’s other linguistic project was Dr. Eldon Lytle’s junction grammar automatic translation software, which we’ve discussed before. This project, funded by the CIA and DoD, became the Missionary Training Center’s language learning curriculum.

***

The ERI lost its tax-exempt status in 1979, getting briefly turned over to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints before being spun off into a for-profit enterprise. The writing was on the wall in 1977, and BYU began dismantling the linguistic project. Without work, the computer translators of the Institute founded their own private companies.

By this point, Weidner’s system was mature. It was translating 450-600 words per hour, compared to 150-200 words per hour needed for human translation. Bruce and his brother Stephen created a network of companies to market the system.

In 1977 they incorporated Weidner Communications, siphoning off a group of ERI programmers and netting $400,000 of initial capital. The Weidners incorporated a marketing company to sell the software, Alta Communications to act as the general partner and Span-Eng Associates for tax purposes. The latter name seems like a reference to Bruce’s earlier translation work. Bruce made a company for himself: Inns of the Temple, Inc. Source 3 claims that the name is a reference to the “London’s Inns of Temple,” showing that Weidner’s work would provide security and support for the Latter-Day Saints into perpetuity. It’s a bizarre thing to say, but this very specific detail leads me to believe that Source 3 had a connection to the whole project.

Initial capital came mostly from the Driggs. They’re a longstanding family of prominence within Mormonism, responsible for founding Driggs, Idaho — a small town nestled at the foot of the majestic Teton Mountains. In 1921 the Driggs family sold everything they owned and relocated to Maricopa County, Arizona. Here, they founded the bank Western Savings and Loans, which remained successful until the late 80s, eventually getting bought out by Bank of America in 1990. Junius Driggs was the CEO of the bank until 1976 when he retired and was named Temple President of the Mesa, Arizona Mormon temple. He turned the keys to the kingdom to his nephew John, who had recently served a stint as the mayor of Phoenix, Arizona. Gary Driggs was the main investor in Weidner Communications, which earned him a spot on the board. Later in life he worked as the president of Western Savings and Loans, ending his career ignominiously with a fraud conviction and two years probation.

Weidner Communications was composed of ERI programmers, while the linguists from the Institute, including Dr. Eldon Lytle, incorporated ALPS in 1979. In terms of actual linguistic benefit, ALPS ended up being more successful.

With Weidner Communications free from Utah non-profit law and the ERI winding down its research projects in anticipation of their upcoming legal battles with the Utah Supreme Court, the Weidner brothers began advertising their translation system to potential customers. Mitel in Canada and the Siemens Corporation in Germany showed early interest, buying prototype versions of English-Spanish and English-German translation software.

Despite a promising start, by 1981 the company was in trouble, laying off one-third of its workers, many of which were poached by rival company ALPS. That same year the Japanese company Bravice bought a controlling interest in the company, looking to optimize English-Japanese translations. This was a futile effort for — despite all the early Messianic promises — the Weidner system produced low-quality translations. Worse still, although the price per word was low, companies had to invest in purchasing IT infrastructure to use the software in the first place. In the end, it was a wash.

While the translation capabilities of Weidner’s software never met their goals, the underlying code could be adapted for monolingual word processing. Now before I tell you this next thing, I want to be clear: this is from the Weidner Communications Wikipedia page. Don’t unsubscribe! The Wikipedia page is pretty weird. It doesn’t have a lot of sources, and is poorly written. In fact, the editors keep wanting to delete the page because it’s shoddy. To me, the tone comes across like somebody who was involved in the company, and didn’t realize that Wikipedia editors don’t count “my personal recollections” as a source. If it’s still up, take a look at it. The thing is pretty detailed. It just doesn’t have many sources — and has a sort of unhinged, borderline paranoid tone.

Honestly, I wouldn’t be surprised if it was written by Bruce Weidner himself, or the author of Source 3, which might be Bruce. Not to belabor the point, but Wikipedia editors recently deleted the Eyring Research Institute page, and there is no doubt the ERI existed.

Ok, so the Wikipedia author claims that the Belgian company Lernout & Hauspie recognized that Weidner’s software could be used for word processing, and sold their copy of the Siemens/Weidner system to a young, but rapidly expanding tech company: Microsoft. They were working on their own word processing software, Microsoft Word, and supposedly the Siemens/Weidner system was reused by Microsoft for this new product. It’s unclear to me how exactly the Siemens/Weidner system was used in the early iterations of Word, but (allegedly) somewhere in your computer is the legacy of David O. McKay’s and Cleon Skousen’s goal to bring Jesus back for his Second Coming.

The Microsoft Word connection is vague, but Weidner’s story heats up when his software made it into another iconic word-processing application: WordPerfect.

****

The story of how the ERI invented WordPerfect is where people’s stories start to contradict. I’ll tell you the official version first, and then Bruce Weidner’s version.

WordPerfect was the most popular word processing software through the 80s and early 90s. Developed for MS-DOS machines, WordPerfect’s market lead only ended with the release of Microsoft Windows. Microsoft didn’t share the API for their Windows OS, allowing Microsoft Word to capture the word processing lead.

The company was founded by two Mormons, Alan C. Ashton (grandson of David O. McKay) and Bruce Bastian. Former WordPerfect executive W.E. Petersen tells the following official company story in his book Almost Perfect.

Bastian and Ashton were computer science majors at BYU when they began developing an idea for word processing software. In the era before widespread home computers, they needed to rent time on a machine to write their code. Being BYU students, they approached the Eyring Research Institute with a proposal. The ERI was already developing a computer system for the city of Orem, Utah. Bastian would write the word processing software for the system, as long as the ERI would pay his salary. Ashton would work for free, but under the condition that the two programmers would own all the rights to their new software.

The two tirelessly worked, completing their software in 1979. Orem got their computer system. Bastian and Ashton founded a new company called Satellite Software International. Orem and the ERI provided seed money. Skipping ahead, SSI was renamed WordPerfect, and the two made themselves filthy rich as they cornered the word processing market. When Word came out, WordPerfect fell into hard times, eventually getting bought out by Novell under the leadership of Dennis Fairclough who — surprise, surprise — was an ERI alum.

Ok, so that’s the official company line. No mention of Bruce Weidner, and the ERI were just the people who provided the computer system and seed money.

Weidner, and other ERI employees like Cleo Harmon, have a different story.

According to Weidner and Cleo Harmon, the ERI recognized that Weidner’s translation software could be adapted to monolingual word processing. ERI president Ronald G. Hansen told Weidner to allow Bastian to convert the Weidner translation software into word processing. Weidner agreed and worked side-by-side with the future WordPerfect founders.

Apparently, Bastian and Ashton were struggling to get their word-processing software correct. Weidner’s code, on the other hand, worked perfectly for word-processing applications, just not so much when it came to translating. In 1979, Bastian and Ashton copied Weidner’s work without his permission and then repackaged it as their software. SSI wasn’t selling something influenced by Weidner — it was Weidner’s work. Bastian and Ashton never mentioned Weidner, cutting him out of future profits. Soon afterward, Weidner was let go from the ERI.

Worse still, Bastian and Ashton were quite good at hiding Weidner’s work. It wasn’t until 1986 that Weidner began hearing that his code was being used in WordPerfect software, and he didn’t have proof until 1999. At that point, he began putting together a court case.

I have my theories as to where the truth lies between these two stories, but I’ll save my conclusions for the end of the article.

*****

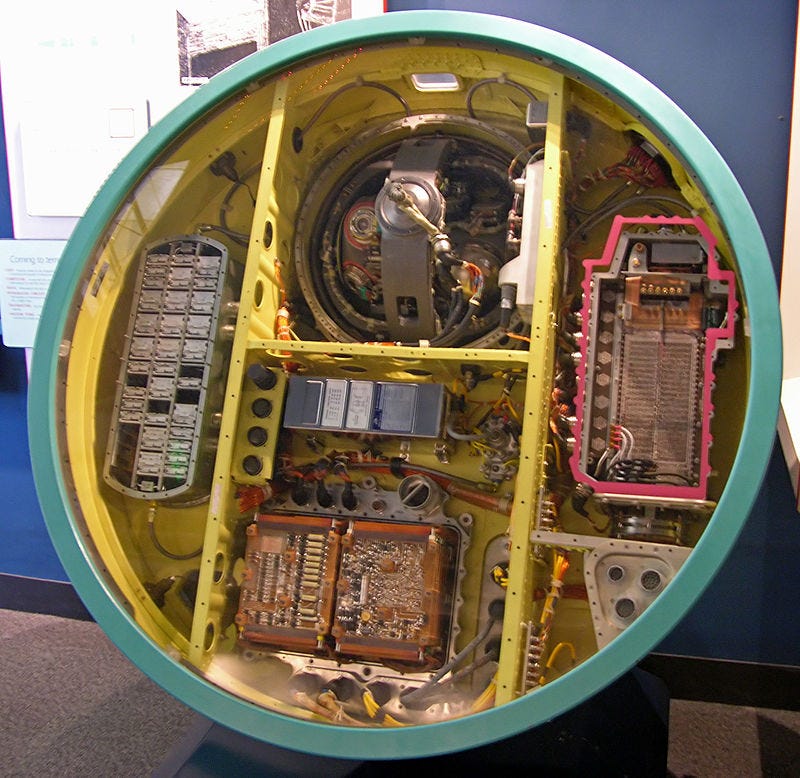

Leaving the world of computer software, I’d like to follow the trail of one of the stranger claims about Weidner’s work. According to later lawsuits, Weidner believes that he helped end the Cold War. In his telling, after his code was stolen in 1979, it was refurbished as nuclear missile guidance software.

Cleo Harmon, the ERI secretary, recollected that in 1972 David O. McKay had brought Weidner’s early work to Hill AFB, the sprawling military complex in Roy, Utah. The Air Force allegedly handed the code over to DARPA. These stories contradict. Weidner says that his code was stolen in the late 70s and then used for missile guidance software without his permission. Harmon says that the Mormon prophet David O. McKay gave the code to the Air Force in the early 70s.

We’re in murky waters now. Of all the parts of a nuclear weapon that the Air Force keeps under wraps, the guidance software is at the top of the list.

So I had to put on my thinking cap.

Hill AFB makes sense as the place where if you were a Mormon prophet or the Mormon prophet’s grandson, you would sell off guidance software. Hill AFB was the home of the Ogden Air Materiel Area (OOAMA.) The OOAMA conducted maintenance and logistics support for the majority of the US Air Force’s strike aircraft and nuclear missiles.

If you’re driving north on I-15, look to the right around the time you hit Exit 335 and you’ll see a white rocket sticking up in the air. That’s an early Minuteman ICBM, the type of nuclear missile that the OOAMA worked on. Now it’s a cheery “monument” to wholesale destruction.

In 1974 the OOAMA was renamed the Ogden Air Logistics Complex (OO-ALC) but still conducted the same mission, including doing maintenance on the LGM-30 Minuteman nuclear missile. Among many projects, the OO-ALC was responsible for upgrading the missile guidance software — it’s a longstanding part of the nuclear missile support cycle. The last upgrade contract was awarded to OO-ALC in 2016.

As I said, the connection here is vague. The only other thing I have to go on is this technical report for Minuteman II missiles that references a study the Eyring Research Institute conducted for the OO-ALC. The ERI did work on the Minuteman missiles, clearly, but did they invent the guidance software? I don’t think so.

******

Back to more linear storytelling.

Bastian and Ashton ended up being wildly successful, only getting derailed when Microsoft pushed its word processor. Of course, even as WordPerfect got replaced by newer software, Bastian and Ashton were still rich.

Continuing the Manichean vibes of this article, the two ended up on opposite sides of the Prop 8 battle. Mormon leaders attempted to influence California politics by commanding church members around the world to donate money and time to get Prop 8 passed, which would have banned same-sex marriage in California. Ashton, following the prophet’s political program, donated $1 million in support of Prop 8. Bastian donated $1 million against.

Weidner resurfaced in 2003, after years of obscurity, bringing a $40 billion lawsuit against Novell and WordPerfect for stealing his software.

Deseret News reported on the story and reached out to Brigham Young University to verify Weidner’s claim that he had worked for BYU and the ERI. BYU says that they have no record of Weidner ever working for them or the ERI, and pointedly stated that the ERI was no longer connected to BYU. This is bizarre, because contemporary documents, including a court case, verify that Weidner was working for the ERI. Why get weird about it and deny any connection? Confirming that Bastian and Ashton didn’t steal the software doesn’t also require denying that Weidner was connected to BYU. It’s overkill. The only way I can figure it is that some legal loophole meant that Weidner technically wasn’t ever working for the ERI. Some of the sources, like this one, are murky whether or not he actually was employed by the ERI, or just knew people there. But still…

Of course, the judge threw out the case, calling it one of the most bizarre lawsuits he had seen. Weidner, however, was not content to let the matter rest. He was a prolific writer, and this is where things get even weirder.

Somebody, who I assume was Weidner himself, attempted to add a Wikipedia page outlining his contributions to machine translation. The Wikipedia editors, citing the 2003 court case, deleted the page.

The Fifth and Sixth Thousand Years — Source 3 — was written pseudonymously by one “Snorri Sturlusson” and contains links to Weidner’s personal writing. Snorri Sturlusson was an Icelandic poet and politician from the 12th century, so I’m going to venture a guess that he did not, in fact, write an unauthorized sequel to a Cleon Skousen book. If the anonymous author isn’t Weidner himself, it’s somebody very close to him.

Weidner’s writings are, to put it bluntly, white supremacist. I didn’t read much — I got the gist of them after seeing how many times he talked about the destiny of the Anglo-Saxon race. Of course, he saw machine translation as the way to bring about whichever mangled white ethnostate he imagined in his head. He is a Skousen disciple, so the millennial reign of Jesus Christ comes with the assurance that Jesus’s reign will install the fascist government of a right-wing Mormon’s dreams.

I located The Fifth and Sixth Thousand Years on a far-right LDS forum. It’s an active place, with members discussing how the teachings of the modern prophets will bring about their ideal government. They did have a problem with current prophet Russell M. Nelson telling people to get vaccinated, naturally.

In the late 2000s, a forum member posted long excerpts from The Fifth and Sixth Thousand Years, claiming they were messages from his “friend Bruce.” We can only speculate, but it seems that in the last few years of his life, Bruce Weidner began styling himself as a religious leader, writing prophecies, and giving messages to his right-wing flock. This poster lists Weidner’s military history:

“142nd Military Intelligence Linguist Co., Utah National Guard, 1960-1962 Recognized as Company's Outstanding Linguist; U.S. Army Military Intelligence School, Ft. Meade, Md., 1960-1961; U.S. Army Language School, Monterrey, California, 1960-1962, Hungarian.

Professionally translated material from Finnish, Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, Dutch, German, Russian, Spanish, French, Italian and Portuguese into English for the CIA’s JPRS, U.S. Army Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence, U.S. Navy”

Weidner died in 2021. His LinkedIn profile lists him as the president of “Worldwide Interlingual Telecom,” a company founded in 2005, but not under Weidner’s name. Notice that this is slightly different from “Worldwide Inter-lingual Telecommunications Utility:” the other obscure Weidner-related company we saw earlier. This specific wording is used in The Fifth and Sixth Thousand Years.

Where does all this leave us?

I don’t think we’ll ever get Bruce Weidner’s full story. Like everything else related to the ERI, once you start digging, you hit rock pretty quickly. It was secretive back in the 70s, and time hasn’t brought any light to their activities.

Here’s what I think happened.

The LDS church was definitely interested in using computer technology to automate the translation of church texts. They saw this as a critical step to bringing back Jesus Christ. The general idea of Skousen and McKay sitting down and theorizing about computers seems right, even if the specific details in The Fifth and Sixth Thousand Years are given a strong messianic twist. Then again, it could be the case of a right-wing nutjob trying to build his credibility by connecting himself to the patron saint of all Mormon right-wing nutjobs.

Weidner most likely worked for the ERI, and he worked on machine translation software. Word and WordPerfect probably used some of his work, but I don’t buy the missile guidance technology. I’m not a computer scientist, but I do know a lot about rockets, and it’s not clear how word processing and missile guidance are similar at all. Clearly, the ERI was doing other work with nuclear missiles, so Cleo Harmon and others might have conflated multiple concurrent projects.

Likewise, I don’t buy the idea that Bastian and Ashton straight up stole Weidner’s work. However, they were all working together, and I’m sure that some of Weidner’s ideas made it into Bastian and Ashton’s work as they all sat together and coded. Computer nerds, after all, like to swap knowledge. That said, David O. McKay was the one who supposedly started Weidner’s project, and his grandson (Ashton) ended up profiting the most from the allegedly stolen software.

BYU is definitely trying to cover something up, and this is a detail that’s difficult for me to fit in with the rest. “Yes, we employed somebody named Bruce Weidner in the 70s, we don’t have any comment about these allegations.” Seems easy enough. Why scrub Weidner? We’ll probably never know.

I also find it strange that most people haven’t heard of the BYU - WordPerfect connection. Out of all the things in this article, that is the one that definitely happened — it’s basically a matter of public record. The Mormons played a critical role in inventing the modern word processor, but I’ve never seen it mentioned in those clickbait “[X] Inventors You Didn’t Know Were Mormon” articles from LDS Living or Deseret News. The Mormons will claim anything vaguely related to them, like that classic myth that Yoda was based on Spencer W. Kimball, or that George Lucas got the idea for the Force after briefly investigating the Mormon church. Had you heard about Bastian or Ashton before reading this article?

As we come to the end of the tale, we’re trailing bits and pieces of stories, allegations, and messianic promises. If you have Word on your computer, somewhere deep in those microchips might be the legacy of the Mormon’s defense think tank and the twisting tale of a Latter-day mad scientist that took the true story of his place in history to the grave.

Bruce Wydner hired ERI. I am the 2nd after Bruce Wydner and can give you the first hand accounts I have. I'll give you the google docs link so you can download the 500+ Bruce Wydner documents.

I’ve got the Bruce Wydner perspective. Let me know.