Twenty-three minutes into the Brigham Young University film The Search for Truth (1962), the movie cuts to Wernher von Braun at the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. The Search for Truth is an apologetics film, filled with interviews with LDS professors explaining how they can be scientists and believe in Mormon theology. Von Braun is the only non-Mormon featured.

He stands in his office, hand on a globe, a model of the Saturn IB behind him, the older brother of the Saturn V that will eventually take the Apollo astronauts to the moon. This is von Braun’s baby, the culmination of a long rocketry career started in Nazi Germany building V-2s, the first operational guided ballistic missile, with concentration camp slave labor. Throughout the last year of World War II, the Nazis rained these missiles over Great Britain, killing 5,500 people. After the war, the US’s Operation Paperclip agents snatched up von Braun and assigned him to develop the rockets for the US’s nascent space and ICBM programs.

But he’s not concerned with rocketry in The Search for Truth. In a flat, oddly high-pitched voice (given von Braun’s generally cubic proportions) he begins talking about the need to develop an ethical system to correctly use atomic power. Ethics, claims von Braun, can only be developed in light of faith in a creator and a belief in immortality. He walks over to his desk, sits down in front of another Saturn IB model and a model of the Rocketdyne F-1 — the future first stage engines for the yet unbuilt Saturn V —, looks at the camera, and says:

Science has found that nothing can disappear without a trace. Nature does not know extinction. All it knows is transformation!

Now, if God applies this fundamental principle to the most minute and insignificant parts of His universe, doesn't it make sense to assume that He applies it also to the masterpiece of His creation — the human soul? I think it does. And everything science has taught me — and continues to teach me — strengthens my belief in the continuity of our spiritual existence after death. Nothing disappears without a trace.

He also published this argument verbatim that same year in an essay in The Third Book of Words to Live By. Nowadays, the quote is most famous for Thomas Pynchon using it (in paraphrased form) as the epigraph for Gravity’s Rainbow.

The Search for Truth is a weird movie. Before the interviews with the scientists, the script runs through the doctrine of Mormon apotheosis. We watch as the sun (“where God dwells”) shines light on Earth. In response, the Earth radiates some sort of wave pattern before turning into a “celestial sphere” that looks like a white dwarf star.

There’s a sketch where Isaac Newton argues with a friend about theism. With the sweeping, yet bland orchestral score over space images, it has a tone eerily similar to the sacred Mormon temple videos (which, as we’ll see below, is not an accident.) But why was von Braun in this? After using concentration camp victims to build rockets to blow up Brits, he found God and became a Christian — but not a Mormon. This is an obscure film; it naturally never achieved the popularity of von Braun’s Disney TV specials. Yet, it might have been the first time von Braun publicly discussed his belief in Christian immortality.

I have found three potential connections where von Braun could have formed a relationship with the Mormons. There are probably more — I couldn’t find proof of this, but I’d suspect Operation Paperclip had some Mormons involved. Maybe it was a random NASA employee who happened to be well-connected, but come on, that’s not very interesting.

Connection #1: The Disney Team

Walt Disney started his career as an entertainer, but as he entered his late career, he focused on the stars and the future. He had already dabbled in utopian technocracy in the 30s when he moved his animation studio from Silver Lake to Burbank. Disney built out his dream studio with a rigid hierarchy, restricting office amenities to higher-paid animators and siloing off the different departments into individual buildings. The Burbank studio was such a dystopian nightmare that it forced the animators to go on strike.

Undeterred, Disney continued his futurist ambitions. With the Space Age starting up, he looked to the cosmos. Von Braun was in the United States now, dutifully building rockets for the country’s armed forces while planning the mission architecture for future lunar exploration. To capitalize on this era of techno-optimism, Walt Disney hired von Braun to star in a series of episodes of the company’s anthology TV series. In the most significant episode, Man in Space, von Braun proposed the technologies that would later launch the Apollo missions. The episode was so influential that it was shown to Dwight Eisenhower and his military rocket scientists. It was their first glimpse of rocketry that was more than glorified, long-range artillery shells.

The director of The Search for Truth, Wetzel O. Whitaker, was a Disney animator through the 40s and 50s and, of course, an active Mormon. After winning a competition to draw Donald Duck, Whitaker was taken in as a full-time animator. Most notably, Whitaker animated the stepsisters in Cinderella. In 1953, he was approached by Ernest O. Wilkinson, the president of Brigham Young University, with the charge of starting a Mormon movie studio to make films for the church. Despite having little equipment or funding, Whitaker agreed. He left Disney, moved to Utah, and became a full-time church employee.

Whitaker’s first film premiered in the October 1954 LDS General Conference. After that, the studio started churning out Mormon movies at a rapid pace, including The Search for Truth in 1962. IMDB includes this anecdote:

“Judge Whitaker, Bob Stum, and Tyler Rogers flew in a chartered twin-engine Piper Apache to Huntsville, Alabama to film Werner von Braun's beliefs about immortality, but found that Dr. von Braun's schedule had been affected by heavy rains, and he would not return for three days. They decided to wait, setting up lights ahead of time. Almost the first thing Dr. von Braun said was, "If I keep up this pace, I will believe in MORTALITY.”

Whitaker’s most important film contract came in 1964 when he was tasked to create a film for the Mormon temple ceremony. The secret Mormon temple ceremony has various handshakes, chants, and robe dressings that the inductees must complete, but the majority of the ceremony is a recreation of the Adam and Eve tale with a Mormon spin. Before the 1960s, the recreation was done with live actors. In the post-war era, with the church expanding into Europe, they couldn’t have actors in multiple languages stepping over each other’s lines while trying to complete the ceremony. A film was the ticket. Whitaker made the movie, and a former Wehrmacht officer turned Mormon temple president completed the translations into the different European languages.

To this day, the church uses a sacred movie in its temple ceremonies. They’ve updated it many times, tweaking the theology presented, updating the special effects, and most recently changing it to a more slideshow-like production. The director for the last iteration being a convicted sex offender seems to have forced the most recent update.

Anyways… the temple ceremony DNA permeates The Search for Truth — it feels like a dry run. But did Whitaker know von Braun before the movie? Hard to say. They almost, but not quite, overlapped in their time at Disney. Whitaker kept up with his old Disney colleagues — for example, one of them showed him the future Anaheim site for Disneyland and hinted that it would be a good place to buy real estate — so it’s not impossible that he met von Braun this way. A more direct connection can be found with Jack Boyd, chief animator for The Search for Truth as well as Man in Space. Still, nothing conclusive.

Connection #2: The Atlas Program

One of the many oddities of The Search for Truth is that the movie is 100% Mormon, except for von Braun. The other three scientists are all active Latter-Day Saints: Armin Hill, Henry Eyring (father of the current third in command of the church), and Harvey Fletcher.

Fletcher is one of the most accomplished Mormon scientists. He collaborated with Robert Millikan on the famous oil drop experiment and went on to invent stereo sound while working at Bell Laboratories. Fletcher’s son, James, studied physics before cutting his rocketry teeth working on missiles for Convair and later joining the Ramo-Wooldridge Corporation to work on the Atlas nuclear missile program. This makes him a contemporary of Wernher von Braun.

When World War II ended, the United States rapidly built a rocketry program to capitalize on the research it had acquired from Nazi scientists. The US Army was an early adopter of rocketry, seeing the new missiles as an upgraded version of old-school gun-and-shell artillery. They had not yet seen the potential of the rocket. Von Braun, however, did. Working in Huntsville, Alabama, von Braun and his group built the Army’s Redstone rocket, a direct descendant of the V-2 they had used during the war. Throughout the 50s, von Braun and his team perfected the rocket, eventually making it dependable enough that when Eisenhower initiated the US manned spaceflight program, the Redstone was chosen as the launch vehicle for the first American astronaut. On May 5, 1961, a Redstone launched Alan Shepard in his Mercury capsule, making the United States the second nation to place man in space.

Interservice rivalry meant that the Air Force was not eager to have the new rockets stay solely the purview of the Army and began a development program of their own. The Air Force missile — Atlas — was also a direct descendant of the V-2. Convair bluntly stated that the new rocket was a “sort of Americanized V-2." The Atlas used liquid fuel and tried a new feature of American rockets: gimbaling the engines to direct thrust for flight control. This had been pioneered by von Braun’s team on experimental V-2s.

Contracting for the Atlas split between Convair and the Ramo-Wooldridge Corporation. The former built the hardware and the latter developed strategic and logistical support. This included working with John von Neumann to create the strategy of Mutually Assured Destruction — as long as the US had enough nuclear missiles, any attempt to attack the country would turn into a worldwide conflagration. The US had unilaterally locked the world into a suicide pact. James Fletcher was a key player, developing system analysis practices for the strategy. Like Redstone, Atlas also played a key role in manned spaceflight, launching later Mercury missions. Between Mercury and Apollo, there was Gemini, orbital missions to develop the techniques needed for a successful moon mission. Of paramount importance was learning how to rendezvous and dock in space. Piloted Gemini capsules were launched on Titans, and Atlases launched the Agena, a passive docking target for the astronauts to train with in orbit.

Eventually Fletcher became the NASA administrator, overseeing the last Apollo missions. At this point von Braun and him worked side-by-side, as seen below. But that was the 70s. In the 60s, Fletcher’s dad and von Braun were just starring in movies together, but perhaps being in competing rocket programs is how von Braun contacted the Mormons. I wrote more about James Fletcher’s career here.

Connection #3: Sperry Utah

The Sperry Corporation was always on the cutting edge of aeronautics. Founded in 1910, the company began inventing airplane instruments, including bombsights and artificial horizons. At the end of World War I, the company invented the Hewitt-Sperry Automatic Airplane, a pilotless biplane filled with bombs. The airplane would take off and dive towards its target — a retrofuturistic precursor of what we now call cruise missiles. In the Second World War, Sperry invented two critical pieces of US bomber technology — the ball turret and components for the Norden bombsight. The former was a small, ball-shaped machine gun turret that protruded from the bottom of B-17 and B-24 bombers, defending the vulnerable underside of the airplane from enemy interceptors. The latter was a complicated analog computer system built into the nose of US bombers. It was designed to let the bomber make precision strikes against targets instead of dropping its bombs haphazardly over civilian areas. In practice, the bombsight’s precision was grossly overestimated.

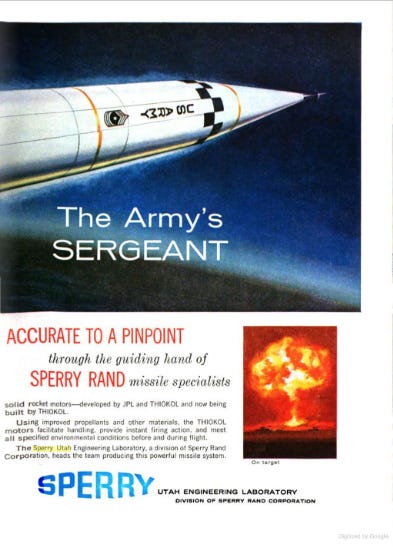

After the war, Sperry decentralized its manufacturing facilities out of fear of Soviet nuclear strikes. One branch of Sperry was sent to Utah — this branch focused on rocket technology. At the same time, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and engine manufacturer Thiokol were working on a short-range surface-to-surface nuclear missile for the US Army. Named the MGM-29 Sergeant, the missile’s design was developed at the Redstone by Wernher von Braun’s team. Once the rocket was ready to go, the Army gave the mass manufacturing contract to Sperry Utah. With Thiokol building the engines and having recently moved its main plant to Brigham City, Utah, the MGM-29 Sergeant was almost exclusively a product of Utah.

Von Braun doesn’t seem to have been too involved in MGM-29 Sergeant production. Frankly, it’s a pretty boring rocket, but it worked. This made it useful for von Braun’s more ambitious project at the time: the Jupiter.

The Jupiter, like most launch vehicles, was developed as a nuclear missile first and a peaceful exploration vessel second. It was built to test euphemistically-named “reentry vehicles,” which just means nuclear warheads. Jupiter followed von Braun’s multistage design philosophy — building rockets out of multiple engine stages, each stage providing the thrust to get the next stage into orbit. The first stage — the stage that gets the rocket off the pad and into the sky — used a Rocketdyne R-7. The next three stages, configured to insert the payload into Earth orbit, were built out of cannibalized Sergeant missiles. Everything unessential was stripped off the rockets as they were clustered together within the fuselage. Jupiter used 14 of these modified Sergeants to get into orbit. Von Braun also used this tactic of clustering preexisting rockets to build the first stage of the Saturn IB.

During early Jupiter tests, the Redstone team had to ballast the nose to push the rocket on a trajectory that would make it fall back to Earth. The United States and the Soviet Union were both racing to put the first artificial satellite into orbit, and nobody wanted the first US satellite to be the nosecone of a Jupiter that accidentally went too fast. But remove that ballast, soup up the engines, and you’ve got yourself a nice launch vehicle. As history shows, the Soviets beat the US into orbit, but von Braun’s team wasn’t far behind. They quickly modified a Jupiter missile for lightweight launches and renamed it Juno I. On February 1, 1958, the Juno I launched Explorer 1 into orbit, starting the United States’s journey into space.

The next time a Jupiter missile would make the news was under much more dire circumstances. The United States Air Force had taken Jupiter and reconfigured it as a medium-range nuclear missile. Since the PGM-19 Jupiter, as it was now called, was not an intercontinental missile, the USAF placed them in France, Italy, and Turkey to have them in range of the Soviet Union. The Turkish and Italian missiles, being right on Russia’s doorstep, convinced Soviet leaders to place equivalent missiles in Cuba, starting the Cuban Missile Crisis. Ultimately, Kennedy removed the Jupiters from Turkey and Italy in exchange for the Soviets removing their missiles from Cuba.

Could Sperry Utah have been von Braun’s connection to the Mormons? His engineering team built the Sergeant, and the Sergeant was used in the Jupiter. Surely, von Braun was in close contact with Sperry Utah during this time.

Wrapping Up

In the end, we’ll probably never know exactly why von Braun starred in a Mormon theological movie, but we can step back and admire the high strangeness of it all. Von Braun was the only non-Mormon featured in the film, but it’s not like the Mormons couldn’t have found other scientists in the country that had a similar theological position. No, this was a case of connections.

From von Braun’s perspective it’s an odd movie to star in. Von Braun converted to Evangelical Christianity, not Mormonism, but I can’t find a similar movie he made for his actual religion. He also never converted to Mormonism. He made this one appearance and then skittered out of the Mormon circle, at least until James Fletcher became NASA administrator.

So what was it about this particular movie that caught his attention, and was important enough that he included the script as a personal essay (or vice versa)? Mormonism, despite its 19th century origins, took on a decidedly space age tone in the mid-century. Notice how prominently space imagery is displayed in The Search for Truth and the sacred temple videos. Or pay attention to the materialist way Mormons conceive of God. They make a special emphasis on the fact that their God has a physical body of flesh and blood, resides on an actual planet, and intervenes corporeally in the affairs of man.

Look back to Joseph Smith’s time and open the Latter Day Saint scriptures to D&C 93:33-34:

For man is spirit. The elements are eternal, and spirit and element, inseparably connected, receive a fulness of joy; And when separated, man cannot receive a fulness of joy.

That sounds like a theological version of the conservation of energy, a concept that was already centuries old by the 19th century, while not often expressed how modern scientists would in the post-Noether’s theorem world.

In his sermons Joseph Smith was less obtuse on this point, and you’ll notice that this is nearly the same argument that von Braun would make a hundred years later:

You ask the learned doctors why they say the world was made out of nothing, and they will answer, “Doesn’t the Bible say he created the world?” And they infer, from the word create, that it must have been made out of nothing. Now, the word create came from the word baurau, which does not mean to create out of nothing; it means to organize; the same as a man would organize materials and build a ship. Hence we infer that God had materials to organize the world out of chaos—chaotic matter, which is element, and in which dwells all the glory. Element had an existence from the time He had. The pure principles of element are principles which can never be destroyed; they may be organized and re-organized, but not destroyed. They had no beginning and can have no end.

The theology is all there, but why von Braun never joined the Mormons will forever remain a mystery. Fortunately though, The Search for Truth hasn’t disappeared. You can watch it here: