The Buried Hero of Desert Storm (ERI Pt. 6)

This is part 6 of my ongoing series exploring the Eyring Research Institute, BYU’s defense and computer research institute. I have written each part so that they can be read independently, but I recommend reading part 1 to get a basic overview of the ERI.

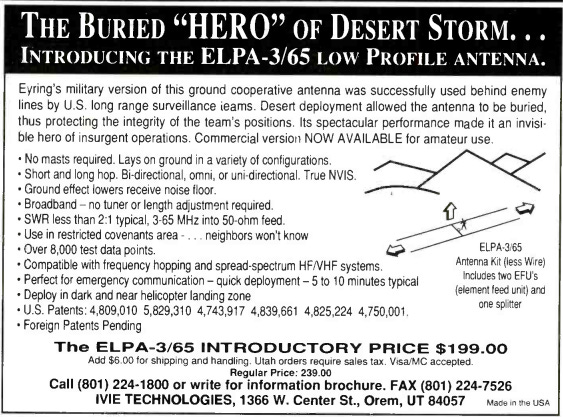

Popular Communications July, 1992:

THE BURIED "HERO" OF DESERT STORM... INTRODUCING THE ELPA-3/65 LOW PROFILE ANTENNA.

Eyring's military version of this ground cooperative antenna was successfully used behind enemy lines by U.S. long range surveillance items. Desert deployment allowed the antenna to be buried, thus protecting the integrity of the team's positions. Its spectacular performance made it an invisible hero of insurgent operations. Commercial version NOW AVAILABLE for amateur use.

In our last installment, I covered alleged psychokinetic research at the ERI. Details were hard to come by, and I had to rely on rumors, innuendos, and a few less-than-reputable sources. In contrast, this is one of the more easily verifiable ERI inventions: the Eyring Low Profile Antenna ELPA-300 series, a cutting-edge battlefield communication device with optional hardening against nuclear strikes.

The Eyring Research Institute had long been interested in communication technologies. Much of their work revolved around software in the form of library systems, automatic translation software, and word processing, but they also got into the hardware side. Searching for the Eyring Research Institute on Google Patent will only pull up patents relating to radio equipment, specifically the hardware that would go into the ELPA-300.

The names on these patents are new to this series. Ferril Losee was an engineer who got his start at the Hughes Aircraft Company, heading the company’s first satellite communication group. Brian Grose went on to create a sonar system for the EDO Corporation, now part of L3Harris.

David Faust and Moray King carried out the fundamental research. We met David Faust in the last installment, working with Eugene Kovalenko on ERI spoon-bending studies and handing over proof of the experiments to David Yurth, an occasional Coast to Coast AM guest and a free-energy pseudoscientist. Moray King also ended up in the free-energy world; a future installment about him eventually. An O.N. Skousen is also listed as a research scientist, a relative of the infamous W. Cleon Skousen, only two generations removed from the Mormon polygamy colonies in Mexico.

King and Faust developed the fundamental theories about how the ELPA would work and an innovative computer test program. Out at the Cedar Valley Test Range in Southern Utah, in the towering mountains flanking the I-15, the ERI crew tested their nuclear-hardened communication system. It was a lucrative contract at the time, with the Department of Defense allocating $800,000 (~$3 million today) for the antenna. With high rugged mountains bracketing flat, arid farmland, and lines of sight extending out to a horizon where new mountain ranges started, Cedar Valley was the perfect testing ground for the ELPA’s special capabilities and future combat use.

Effective combat communication is essential in modern warfare, but deploying the equipment is tricky. You can’t just erect a big radio mast in the middle of a combat zone: that’s a quick way to give away your position. Discrete, portable radio equipment is limited in range and frequency availability, especially before widespread space communications. The ELPA bridged the gap, providing a wide selection of high-frequency to very high-frequency communication bands while remaining man-portable. Usually, these frequencies required a big radio antenna, but the ELPA was clever: instead of erecting a mast vertically, lay the antenna sideways on the ground. It was a remarkable feat to make this work. An antenna standing straight up can transmit above the ground, but the ELPA had to work around and through intervening terrain.

To set up the ELPA-300, a soldier simply had to unspool two 300-foot wires, place them 20 feet apart, and connect them to various bits of electronic hardware. The wires could be placed as low as 1 foot above the ground or even underground, although that came with some reduction in capability. The whole setup was portable, fitting within a small pack. This meant that an ELPA-300 could be used in a tactical setting without pre-existing infrastructure. Just unspool the wires, and you immediately have HF/VHF communication capabilities without having to build a tower that could take time and give away your location. The low profile and easy setup also meant that it could be deployed at night, in adverse weather conditions, and in the middle of helicopter landing zones.

Being low to the ground also gave the ELPA-300 around 180 degrees of coverage, referred to as a “take-off angle.” In its primary tactical deployment, the ELPA would direct its radio beams at a nearly vertical angle, establishing skywave communications. This communication mode takes advantage of the charged ions in the atmosphere to bounce the radio beam to targets beyond the local horizon, giving the ELPA an extremely long range. Conversely, the ELPA could also direct radio beams along the ground for 25 miles.

Between these communication modes, the ELPA could also establish line-of-sight communications between itself and another radio receiver, useful for soldiers on a mountaintop attempting to communicate with other troops down in a valley and air forces in the sky. In this mode, the ELPA is a communication link useful for calling in air support during a firefight. The mountains of Cedar Valley were a good testing ground for this, and the terrain of Iraq was the ideal application. In Desert Storm, Army long-range reconnaissance units relied on the ELPA for communications, especially when they were behind enemy lines. Any other antenna would have given away its position.

The figure below shows the wide range of ELPA capabilities. The shaded zones are the angles within which the ELPA works. You can see that the ELPA can transmit basically from horizon to horizon, with only two narrow dead bands.

Besides the flexible coverage, the ELPA was also highly survivable. It could be deployed on top of the soil and even underground. Snow provided no problem for the antenna, the device still worked in an urban setting, and it even could transmit in a jungle, but only limited to the straight-up near-vertical incidence skywave mode. It could even survive a nuclear blast.

While the operating manual only mentions the nuclear survivability off-handedly as one of the antenna’s characteristics, advertisements for the civilian version tagged this as a key feature. Page 51 of the ELPA manual points out that the antenna can shrug off a lightning blast or a high-altitude electromagnetic pulse. EMPs are produced by exploding a nuclear weapon at high altitude or in space, blanketing huge portions of the globe in electromagnetic radiation and frying any electronic components underneath. However, the ELPA did not come nuclear hardened out of the box, or at least it didn’t in the military version. If the military wanted their antenna to survive a nuke they had to buy an extra conversion kit from the Eyring Research Institute or the PolyPhaser corporation, an electronic firm specializing in surge protection. At the time they were headquartered in Minden, NV, a small town so backward that it had a sundown siren until 2023. Now they work out of Hayden, Idaho in Kootenai County.

The Army wasn’t the only party interested in the ELPA. David Faust’s computer test program was developed under the auspices of the Rome Laboratory, the U.S. Air Force's main lab for command, control, and communication technology research. The Navy put the antennas on their vessels, with David Faust appearing in a distribution list for a survey of combat survivable HF/VHF antennas.

The ERI also licensed out the antenna for civilian marketing, renamed as the ELPA-3/65. The Ivie Corporation in Springfield, Utah was given the license and began marketing their antenna. They don’t seem to sell it anymore, at least from what I can tell from their website. In the civilian guise, the ELPA emphasized the same characteristics that made it useful for tactical operations behind enemy lines, which is odd for a piece of equipment ostensibly geared toward radio amateurs.

Take a look at the Popular Communications ad. Alongside the technical specs, it lists advantages like “use in restricted covenant areas… neighbors won’t know” and “deploy in dark and near helicopter landing zones.” How many amateur radio enthusiasts need the capability to set up VHF communications in a helicopter landing zone?

Another ad, recorded here, tells users that the antenna is nuclear survivable and perfect for high-frequency tactical communications. They emphasize that even if you are in an RV park or apartment you can set up the antenna in a few minutes, transmit your message, and then pack up the gear quickly.

Between these weird advertisements and the fact that the nuclear hardening equipment came from a company that has worked out of a racist Nevada town and the militia-ridden mountains of Northern Idaho, it almost seems like the ELPA-3/65 was being marketed towards prepper-types at best, or paramilitary organizations at worst. Of course, that’s just speculation.

Loose Ends

Whenever I am looking at Mormon weapons development, the prospect of Armageddon is always at the back of my mind. Having grown up with a worldwide war just over the horizon — and Jesus’s return imminent — the future always looked like mushroom clouds, my family slowly meting out our food storage to survive the cataclysms, or taking to the road with our 72 Hour Kits that we spent a Monday night putting together.

Jesus’s Second Coming is perhaps the most important theological position the modern church takes — it’s what the “Latter-day” in the official name refers to. But the church isn’t passively waiting on Jesus to return, active preparation is repeatedly emphasized over the pulpit. The Mormons, after all, are expected to lead the non-believers in the Last Days.

So when the manual and civilian advertisements both make a big deal out of the nuclear survivability, it gets me looking for more signs of Apocalyptic preparation. Here’s an extra handful.

Alongside the ELPA, the Eyring Research Institute scientists also investigated protecting other devices against blasts and radiation. They conducted research into protecting photovoltaic cells from radiation and hardening electrical connectors.

The ELPA might have had a wider frequency range than published, or at least the design of the antenna could be easily adapted to access other frequency bands. The patents relating directly to the ELPA reference a patent from the 60s demonstrating how to create an extremely low-frequency antenna using a configuration similar to the ELPA. In our last installment, we saw that the ERI was interested in ELF radio waves for communication purposes and as a potential vector for psychokinetics. ELF waves are mainly used to communicate with submarines.

The Navy TACAMO program operates airplanes as airborne communication posts, specifically designed to survive a nuclear strike and continue communication with U.S. forces, even submarines underwater. Professor Dick Adler was an electromagnetic expert whose students went on to work on the TACAMO program. Dr. Adler also worked with the Eyring Research Institute to research antennas near the ground or on irregular terrain, like the ELPA. Dr. Adler was instrumental in the Polar Equatorial Near Vertical Incidence Experiment, an experiment to use near-vertical incidence skywave propagation techniques in the Arctic. This was also one of the ELPA’s communication modes.

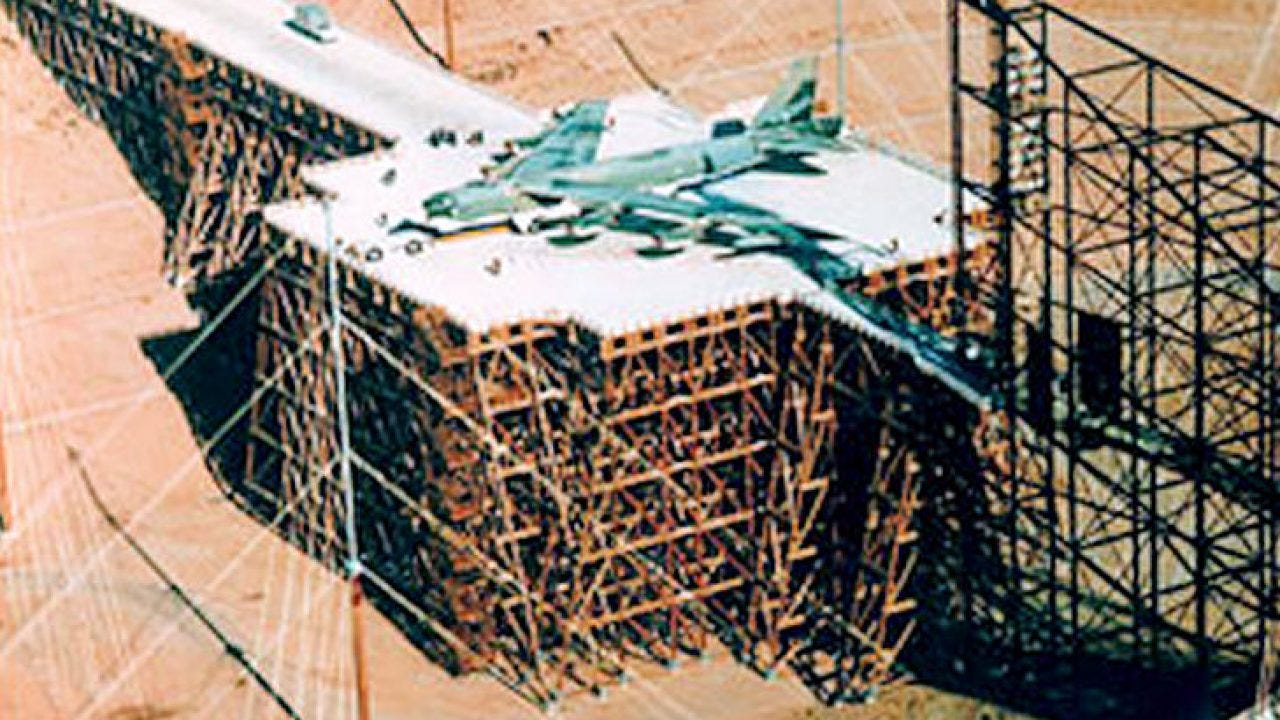

Dr. Carl E. Baum was a scientist specializing in electromagnetic pulses. He built the Trestle, the largest EMP testing rig. The Trestle was used by the Air Force to investigate hardening aircraft systems against EMP pulses. The rig was big enough to place a fully loaded B-52 bomber on it and powerful enough to create EMP pulses as damaging as a nuclear bomb. In his notes, he cites one of the Eyring Research Institute’s earliest papers, Fields in a Rectangular Cavity Excited by a Plane Wave on an Elliptical Aperture. A Navy report detailing aircraft electromagnetic design techniques also cited this paper. This is the first time I’ve seen Harvey Fletcher, a renowned physicist and father of NASA Administrator James Fletcher, show up in connection with the ERI.

David Faust and Moray King went on to spend a lot of time with David Yurth. Together, the team left the real-world scientific community behind and began exploring more esoteric communication devices. According to Yurth, Faust invented a way to communicate faster than light using the non-local principles of quantum mechanics. Faust also invented a way to block gamma radiation (that was apparently unreproducible) and transmit nuclear energy through the air. Moray King went on a free-energy kick that I plan to cover in more detail in the future. Despite picking up some genuine interest from the Department of Energy, Yurth and Faust found their “scientific” research sidetracked by a securities fraud investigation that seems to have been ongoing in 2015.

It’s always this way with these ERI guys. You find yourself diving through a dry technical manual, and suddenly they’re claiming to have invented faster-than-light communications.